BookPick: A Home on the Rolling Main

Posted on May 31, 2014 Leave a Comment

[To leave a comment or reply go to box at the end of the page]

I always enjoy naval memoirs and Tony Ditcham’s has to be among the most engaging I’ve read recently.From first joining the Royal Navy in 1940 until the end of the campaign against Japan, Ditcham was in the front line of the naval war. After brief service in the battle-cruiser Renown off Norway, he went into destroyers and saw action in most European theatres against S-boats and aircraft in ‘bomb alley’ off Britain’s East Coast, on Arctic convoys to Russia, and eventually in a flotilla screening the Home Fleet.

During the dramatic Battle of the North Cape in December 1943 from his position in the gun director of HMS Scorpion he had a grandstand view of the sinking of the great German battleship Scharnhorst. Later his ship operated off the American beaches during D-Day, where two of her sister ships were sunk with heavy loss of life, and he ended the war en route for the British Pacific Fleet and the invasion of Japan.

Ditcham tells his story with humanity, humour and a seaman’s respect for Neptune’s realm. Sadly, as the surviving veterans rapidly decline in numbers, this may turn out to be one of the last great eyewitness narratives of that conflict. The ‘Naval Review’ was fulsome in its praise:

- ‘As a story of World War II at sea, seen through the eyes of one young man growing up, this is, and I do not think I am exaggerating, a masterpiece.’

I think I have to concur.

Published by Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-175-5

Who Really Sank Bismarck, the Pride of Hitler’s Fleet?

Posted on May 27, 2014 38 Comments

[To leave a comment or reply go to box at the end of the page]

Iain Ballantyne’s blog on submarines of the Cold War generated quite a deal of interest so I’m delighted to welcome Iain back again as a Guest Blogger, this time his topic is slaying the myths of the battleship Bismarck. Iain has released a paperback edition of ‘Killing the Bismarck’ which provides some fascinating updates to his earlier hardback and is justly recognised as the definitive account of the British part in the battle.

Over to Iain…

The Atlantic, 27 May 1941

The smoke over the water had not long dissipated, the fire snuffed out and thunder only just faded. The wrecked battleship Bismarck was now lying on the floor of the ocean, the majority of her crew killed aboard or drowned.

The British battle-wagon HMS Rodney sailed away from the scene of combat in company with the Home Fleet flagship HMS King George V. It was Rodney’s massive 16-inch guns that did the close-up killing of Bismarck.

In a mess deck aboard Rodney a rating composed a piece of doggerel –- ‘Within the span of seven days

From view to chase and kill

The pride of Hitler’s Navy learned

The might of Britain’s will’

If you believed this triumphant verse, it was all pre-ordained and those impudent Germans should have known better than challenge an island nation that had ruled the Seven Seas for centuries.

In some ways Rodney’s sailor wasn’t wrong. The Germans had sent out their newest, most powerful battleship along with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen to destroy Allied convoys. While delivering a serious blow by sinking the battlecruiser HMS Hood on 24 May, the Germans soon discovered the Royal Navy could soak up disaster, spring back and bring its still considerable might to bear.

The reality is that no warship is unsinkable, no navy can totally control the oceans, but the British had more experience and a bigger, better-balanced navy than Hitler had allowed his admirals to create.

However, if you are to believe today’s majority perception of the Bismarck action the German battleship was unsinkable – in fact, she was so strong and invincible that it wasn’t the British guns and torpedoes that sank her, but her own scuttling charges.

Debate has raged for years around this point, making it the focus of underwater investigations on Bismarck’s wreck. Some found ‘proof’ that scuttling sank her; while others have offered evidence she was already sinking due to the holes caused by British shells and torpedoes.

The mighty 16-inch guns of HMS Rodney – the weapons that destroyed Bismarck.

Credit: US Naval Heritage and History Command

But sea battles are not a game of top trumps, comparing calibres of guns and flaws in naval architecture. What matters is the human element and in that respect Bismarck was defeated before her final battle. Her men were utterly demoralized by being harassed across the ocean by the British. They had experienced a huge high after destroying Hood on 24 May but by 26 May were in a deep depression. They regarded the admiral in charge of their raiding mission as a Jonah and saw their chances of reaching a safe port as virtually zero. After the Swordfish attack that destroyed their vessel’s steering, many in Bismarck’s crew just gave up.

And this brings us to the key element of controversy that my book ‘Killing the Bismarck’ presents, namely the contention that some of her crew tried to surrender at the height of the battle. When the hardback edition was published, and the surrender angle received national newspaper coverage, this caused outrage – from the USA and UK to Poland – among the ranks of those who still believe in the ‘invincible Bismarck’ myth.

One thing I have learned over the past decade or more that I have been writing naval history books is that the accepted view of how events happened often collapses, or at least can sometimes prove open to question, when you go deep into the archives.

With regard to the Bismarck action I looked at the ‘surrender’ claims via three different accounts. I found one (by a Rodney officer) in the archives of the HMS Rodney Association. In another, the son of the man involved (a rating in Rodney) volunteered transcripts and sound recordings. The third, from a sailor in the cruiser HMS Dorsetshire, was in the archives of the Imperial War Museum. The signs that these men saw included a man sending a signal via semaphore, mysterious light signals and a flag raised that seemed to indicate a desire to ‘parley’.

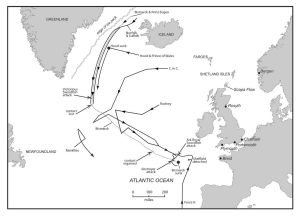

Battle map showing the scope of the Bismarck action from 23 May 1941, when Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were shadowed by British cruisers, through the Battle of the Denmark Strait, on 24 May, to the final clash on 27 May

Copyright © Dennis Andrews

The British sailors I quote were in a very good position to see what was happening. They were in action stations with an excellent view of the enemy and certainly in Rodney’s case they had high-powered optics and could see with shocking clarity what was happening. I don’t think people realize just how close Rodney was in the final moments. The men who were best able to see what was happening in the fore part of Bismarck were sailors in British warships, not German survivors. The latter mainly came from well-protected engineering spaces deep within the citadel or served in the equally robust main armament turrets aft.

Was it possible for the British to take Bismarck’s surrender? No. Some sailors may have been trying to surrender in the fore part of the ship, but their shipmates elsewhere continued to fire on the British. Was it an attempt to surrender on authorization of Bismarck’s commanders, or just an initiative by some sailors who understandably wanted the killing to stop? Nobody will ever know for sure. No battleship deep in the heat of action has taken the surrender of another, at least not since the end of the wooden walls.

Rodney and King George V were two very important capital ships. The British didn’t have many and the Royal Navy was in May 1941 taking a hammering in the Mediterranean during the Battle of Crete. Bismarck’s sister battleship, Tirpitz, was expected to set sail at any moment while there were other German high seas raiders lurking in Brest, waiting to come out and savage Allied shipping.

To risk King George V and Rodney would have been a gigantic strategic error. Bismarck’s ensign continued to fly, she was still firing and for the sake of Britain’s security she had to be destroyed as a fighting entity. After the guns ceased firing on both sides – and it’s worth pointing out the Bismarck’s guns did not fall silent until the British put them out of action – it was a different matter. The brotherhood of the sea saw the hand of mercy extended.

The most controversial element of the fresh material in this edition of ‘Killing the Bismarck’ is an account by an aviator who took part in the May 26, 1941 attack on the German battleship that fatally damaged her steering. Terry Goddard was a young Observer in a Swordfish of 818 Naval Air Squadron. Until he got in touch with me I thought John Moffat was the only living veteran of that crucial episode.

Terry, who is now 94-years-old, read the hardback edition of ‘Killing the Bismarck’ and emailed me offering an account he had written of his part in that mission, which I present as the headline element of new material in the paperback.It does contradict some recent claims about whose Swordfish torpedo did the fatal damage to the German battleship. History is organic, and ever evolving, with fresh perspectives to be discovered even now more than 70 years on from the Bismarck action.

I was also pleased to be able to present material from another surviving veteran, who back in May 1941 made a transatlantic passage in Rodney as a 17-year-old midshipman. There is also a blow-by-blow account freshly rediscovered by the son of a Royal Marine officer who served in the gunnery director position of the cruiser Norfolk.

Of course as the years go by the opportunity to encounter veterans of the Second World War is diminishing rapidly, so I doubt very much there will be another edition of ‘Killing the Bismarck’ that presents fresh eyewitness material on top of that already discovered. However, even as the paperback rolled off the presses, I heard of another veteran who may have a story worth telling and who is still with us…

‘Killing the Bismarck’ is published by Pen & Sword. I have three copies of the paperback to give away. To go into the hat, email julian@julianstockwin.com with the name of the naval current affairs magazine of which Iain is currently editor.

Please include your full postal address. Deadline: June 3. Winners will be notified by email.

Iain is the author of seven naval history books. His most recent hardback is ‘Hunter Killers’, Orion Books.

Iain’s website

COMMAND: the watershed book

Posted on May 23, 2014 5 Comments

A regular feature looking back on each of the Kydd titles – with story background, research highlights, writing challenges and more.

In this book, newly commissioned Commander Kydd is thrilled at his first command, a little brig sloop called Teazer – but when peace is declared he finds himself on the beach

Watershed book

In many ways COMMAND is a watershed in the Thomas Kydd series. My hero has actually achieved the majesty of his own quarterdeck, and his life will never be the same again. It may seem an improbable transformation of a young perruquier of Guildford, press-ganged into His Majesty’s Navy less than ten years before, but the historical record tells us that there were ‘Thomas Kydds’, only a handful admittedly – but enough to be tantalising to a writer’s imagination. Yet we have so few records of their odysseys – how they must have felt, what impelled them to the top…Was there one particular person on whom Tom Kydd was modelled?

The answer is no. He is a composite, the result of my author’s imagination. But in him there are certainly elements of those like William Mitchell, a seaman who survived being flogged around the fleet for deserting his ship over a woman – 500 lashes – and later became an admiral; Bowen of the Glorious First of June, and others – in Victory at Trafalgar her famous signal lieutenant, Pascoe, hailed from before the mast and the first lieutenant, Quilliam, was a pressed man, who like Kydd was promoted from the lower deck at the Battle of Camperdown.

The great age of fighting sail was a time of huge contrasts and often very hard conditions – but in the Royal Navy then it was conceivable for a young man of talent and ambition to rise far above his station.

I remember my own feelings when I became an officer, having begun my sea career on the lower deck. And sometimes I wonder, had I lived back then, could I have been a Tom Kydd? It’s a pleasant thread to follow in idle moments but I think I enjoy my creature comforts too much. They really were iron men in wooden ships!

Research in Malta

Research for this book took me to the island of Malta where I had the pleasure of meeting Joseph Muscat whose encyclopaedic knowledge of Mediterranean craft was invaluable. Joseph presented me with a copy of his magnum opus of sea vessels from 1600 BC to 1900 AD, ‘Sails Round Malta’, which has a special place in my library.I was also delighted to have the opportunity to spend time with Reuben Lanfranco, director of the prestigious Maritime Institute of Malta.

Remote Van Diemen’s Land

Of course I knew Tasmania (then Van Diemen’s Land) well, having lived and worked there – and married a local girl! This knowledge was topped up by my Australian researcher Josef Hextall, who provided material on the early days of Sydney Cove. Even today there are parts of Tasmania largely untouched, just as in Kydd’s day. I remember exploring remote parts of the coast in my little boat Galah.Praise for COMMAND

Readers have been very fulsome in their comments about COMMAND, including some who have experienced the special challenges of command themselves.

One retired colonel in the US airforce emailed:

- ‘I’ve enjoyed watching the development of the character of Tom Kydd as he progressed from the time of his impressment. Having spent almost 35 years in the military, and like Tom rising from the ranks, I felt sure of his direction …but the story is “in the journey” and you continue to chart an adventurous, but believable course for Tom. For me, having walked a somewhat similar road, just in a different age of weaponry, that’s the key…is it believable? Command adds that major factor of “total authority AND total responsibility” to this continuing adventure. From my perspective, your personal insight has provided your readers with a credible picture of the best, and worst features that accompany command.’

The book’s cover art

My editor commissioned an original oil painting by Geoff Hunt RSMA for the cover of this book. It’s one of my favourites!

Geoff had painted brig‑sloops before, most notably Patrick O’Brian’s Sophie. As usual, he undertook extensive research before even picking up his brush. This is what Geoff says:

- ‘Teazer is a small, handy, fast vessel, almost yacht‑like, very much a young man’s command. I wanted to get over this feeling of excitement, brio, high performance – reflecting Kydd’s own delight in his first real command. ’

Geoff’s superb painting is available as a limited edition print.

Royal Reader…

And I had the great honour of presenting a copy of COMMAND to HRH The Princess Royal when she viewed a model of Teazer at the opening of the Ivybridge Library.This beautiful craft was presented to me by John Thompson of Merseyside in appreciation of my books – eight hundred and fifty hours in the making and has pride of place in my home.

Hard to top that!

(Here you can read my previous post, on TENACIOUS)

BookPick: Warship 2014

Posted on May 20, 2014 1 Comment

[To leave a comment or reply go to box at the end of the page]

The 36th edition of this annual maintains well-established standards of scholarship, research, news and reviews from the field of warship history. It features in-depth articles on a range of diverse subjects including a detailed technical description of the very large projected carrier designated CVA-01 and a review of the careers of Germany’s Braunschweig and Deutschland classes. Also included are — the development of the Italian aircraft carrier Cavour; the conception and characteristics of the armoured cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy; an unusual account of the escape of the Jean Bart from Saint-Nazaire; the history of Russia’s turret frigates of the Admiral Lazarev and Admiral Spiridov classes – and an examination of the post-war evolution of fire control in the Royal Navy. This last article was of particular interest to me as much of what it covered was still in practice during my own time at sea.

I particularly enjoyed the sections at the end of this year’s annual – Warship Notes, snippets of warship history; Gallery, photographs of the building of the French battleship Liberte and Naval Books of the Year – a fine selection of titles covering topics ranging from the Roman Navy to French carriers of the 1950s.

Published by Conway Maritime. ISBN 978 1 84486 236 8

Why Jane Austen Loves a Sailor

Posted on May 14, 2014 2 Comments

[To leave a comment or reply go to box at the end of the page]

This month saw the paperback launch of ‘Eavesdropping on Jane Austen’s England’ by Roy and Lesley Adkins. The book is a fascinating and spirited account of life ashore in Kydd’s day.

I had the pleasure of meeting the Adkins in person last year and was delighted when they agreed to pen a Guest Blog for me on Jane Austen and the Navy. It seems particularly appropriate to run it this month, to mark the 200th anniversary of the launch of ‘Mansfield Park’.

Over to Roy and Lesley…

Jane Austen lived from 1775 to 1817, and for two-thirds of her lifetime Britain was at war, though that barely features in her writing. Instead, she followed the maxim of ‘write what you know about’ by devising contemporary novels, full of humour and populated by the gentry and upper classes. Her readers were of the same class and needed no reminder of the wars.

Austen’s novels describe the dilemma of marrying for love or money, young women seeking husbands, elopement, divorce, duty and status. Two of her titles, MANSFIELD PARK and PERSUASION, contain her most appealing characters – naval officers – revealing her love affair with the Royal Navy. By the time her books were published, the nation was also in love with the navy, because of its victories under Nelson at the Nile, at Copenhagen and at Trafalgar.

Mansfield Park’s plot concerns Fanny Price, whose parents in Portsmouth are too poor to cope with all their children. Although from a respectable family, her mother had married a mere lieutenant of marines (which Jane Austen intends as a joke, knowing how marines were regarded by seamen). Fanny goes to live with her wealthy aunt and uncle at Mansfield Park in Northamptonshire, while her favourite brother, William, joins the navy as a midshipman. It is William who stands out as the most congenial and unpretentious character.

The only rogue naval man is Admiral Crawford, who is living openly with his mistress since the death of his ill-treated wife. This is surely a comment on Nelson, who deserted his wife Frances for his mistress Emma Hamilton. Just as the public adored Nelson, we can’t help warming to Admiral Crawford when he helps William Price obtain promotion.

In the summer of 1815, Jane Austen began writing PERSUASION, which has even more of a naval theme and is set just after Napoleon’s overthrow in 1814. The snobbish Sir Walter is so much in debt that he moves to Bath and lets his mansion to the likeable Admiral Croft, whose brother-in-law, Frederick Wentworth, was once engaged to Sir Walter’s daughter Anne.

She was persuaded to cancel the engagement as Wentworth was deemed too lowly a naval officer. He has now returned from the wars as a captain with a fortune in prize-money. Although not brought up in a naval household, Jane Austen has an authentic voice. Her knowledge came mainly from her brothers Frank and Charles. They were naval officers, and she took a keen interest in their careers. They in turn introduced her to their naval friends, and numerous letters were written whenever they were away. She herself travelled a great deal, visiting friends and relatives and no doubt meeting other naval officers at dances and dinners.

For over two years, from 1806, Jane Austen, her sister Cassandra and their mother lived with Frank and his wife at what was then the small seafaring town of Southampton. From here Jane could have visited Portsmouth and its dockyard, providing the background for scenes in Mansfield Park. Her familiarity with the navy even extended to seeing warships being built, as in a letter of November 1808:

I and my two nephews went from the Itchen Ferry up to Northam, where we landed, looked into the 74, and walked home

This visit was to the nearby Northam yard to view the 74-gun Conquestador being built. The warship was launched almost two years later, after the Austens had moved to north Hampshire.

A large cottage (now a museum) in the village of Chawton became their new home, situated alongside a busy road to Gosport and Portsmouth. Close by lived the Prowtings, and the Austens came to know them well. In October 1811 their daughter Ann-Mary married Captain Benjamin Clement, and the couple settled in Chawton. According to Cassandra, Mansfield Park was begun earlier that year, though much of it was probably written after the Clements became neighbours. It is tempting to think that Jane was partly inspired by tales related by Captain Clement, who was a Trafalgar hero.

At Trafalgar Clement was a lieutenant on board HMS Tonnant. During the height of the battle, Tonnant encountered the damaged Spanish ship San Juan Nepomuceno, which surrendered after a short exchange of fire. Clement told his father what happened:

I came aft and informed the first lieutenant. When he ordered me to board her, we had no boat but what was shot, but he told me I must try; so I went away in the jolly boat with two men, and had not got above a quarter of the way, when the boat swampt.

Like many seamen, Clement could not swim:

the two men that were with me could, one a black man, the other a quarter-master: He was the last man in her, when a shot struck her and knocked her quarter off, and she was turned bottom up. Macnamara, the black man, staid by me on one side, and Maclay the quarter-master on the other, until I got hold of the jolly boat’s fall that was hanging overboard.

Clement feared he would die, but Macnamara swam to bring him a rope, and he was hauled to safety.

Captain Clement, his wife and sister-in-law are referred to in perhaps the last letter written by Jane Austen before she died at Winchester. Only fragments of it are known, published by her brother Henry, who omitted names:

You will find Captain — a very respectable, well-meaning man, without much manner, his wife and sister all good humour and obligingness, and I hope (since the fashion allows it) with rather longer petticoats than last year.

The comment ‘without much manner’ is possibly criticism, and Jane was certainly lukewarm in an earlier letter:

In consequence of a civil note that morning from Mrs Clement, I went with her and her husband in their tax cart. Civility on both sides. I would rather have walked, and, no doubt, they must have wished I had.

It may have been difficult for Jane to live close to a Trafalgar hero, knowing that Francis had narrowly missed the battle. A year older than Jane, he had entered the Royal Naval Academy at Portsmouth in 1786 and two years later joined his first ship. He gradually worked his way up the ranks to become flag-captain of HMS Canopus, an 80-gun warship. He actually wanted to be a frigate captain, desperate for more independence and prize-money. Instead, in October 1805, he was off Cadiz blockading the port. Just when the French and Spanish ships were expected to leave Cadiz and engage in battle, Nelson ordered Canopus to sail to Gibraltar for supplies. Frank missed the battle, the glory and the prize-money.

Jane Austen knew all about the difficulties of gaining prize-money and promotion, themes that occur in these naval novels. Frank did rise through the ranks, eventually becoming Admiral of the Fleet, but could never claim the coveted distinction of being a Trafalgar hero.

Canopus was immortalised in Mansfield Park, because when William Price returns to Portsmouth, his mother says that his ship, HMS Thrush, is ready to sail. William fears he will be left behind:

I had better go off at once, and there is no help for it. Whereabouts does the Thrush lay at Spithead? Near the

Canopus?

While writing Mansfield Park, Jane wrote to Frank, then captain of Elephant:

Shall you object to my mentioning the Elephant in it, and two or three other of your old ships?

In the novel, William’s father says:

Captain Walsh thinks you will certainly have a cruise to the westward, with the Elephant.

He next tells William that Thrush lays close to the Endymion , between her and the Cleopatra , just to the eastward of the sheer hulk

Cleopatra and Endymion were ships of Jane’s younger brother Charles. He had entered the Naval Academy in 1791 and joined his first ship three years later. From 1804, he served for years on the North American station, eventually taking command of the 32-gun Cleopatra, which he sailed back to England in the summer of 1811.

A decade earlier Charles was patrolling the Mediterranean in the frigate Endymion:

The Endymion came into frequent contact with the enemy’s gunboats off Algesiras, and assisted in making prizes of several privateers. On the occasion, particularly, of the capture of the Scipio, of 18 guns and 140 men, which surrendered during a violent gale, Charles Austen very intrepidly put off in a boat with only four men, and, having boarded the vessel, succeeded in retaining possession of her.

Many months later, as a reward for capturing this and other vessels, Charles received prize- money, from which he purchased jewellery for his sisters, as Jane told Cassandra in May 1801:

He has received £30 for his share of the privateer & expects £10 more, but of what avail is it to take prizes if he lays out the produce in presents to his sisters. He has been buying gold chains & topaze crosses for us.

The treasured topaz crosses are today displayed in the Chawton museum. The incident is echoed in Mansfield Park when William Price buys a cross for Fanny:

a very pretty amber cross … William had wanted to buy her a gold chain too, but the purchase had been beyond his means

He later shares with Fanny his

speculations upon prize-money, which was to be generously distributed at home, with only the reservation of enough to make the little cottage comfortable, in which he and Fanny were to pass all their middle and latter life together

Such were the dreams of seamen – to earn sufficient prize-money to buy a cottage or public house. Less charitably, William admits that the first lieutenant needs to be ‘out of the way’ so that he can fulfil his dreams, which is the same sentiment as the officers’ toast: ‘A bloody war and a sickly season’, hoping for events that will kill off those above them and lead to promotion.

Thomas Kydd meets Jane’s brother Francis in INVASION. For a chance to win one of three paperbacks of ‘Eavesdropping on Jane Austen’s England’ email julian@julianstockwin.com with the name of the naval militia with which Francis was associated. Please include your full postal address.

Deadline: May 21

Copyright notices

Book image: By Jane Austen (1775-1817) (Lilly Library, Indiana University) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

Great Granny Annie’s Recipe

Posted on May 10, 2014 12 Comments

I take great pains with the authenticity of the Kydd books, visiting the locations in the tales for extensive on-site research, poring over charts and maps, checking technical specifications regarding Age of Sail seamanship and consulting experts in all kinds of arcane fields. It’s a big investment in terms of time and money but a part of the writing process that I find most pleasurable. And I particularly enjoy hearing from readers who in some way have a special connection with the Kydd books. This has ranged from a guide aboard HMS Victory to yachtsmen in the Caribbean who have recreated Kydd’s journeys, to a reader born and raised in Guildford, Kydd’s home town.

The May Reader of the Month, Sybil Galbraith, is one such reader. Sybil now lives in the small village of Glenfarg in central Scotland but grew up in the late 50s in South Africa. An artist and student of family history, Sybil was drawn to the Kydd series when she saw a copy of CONQUEST aboard the Perth and Kinross mobile library service van and picked it up, intrigued by the story location. Sybil told me: ‘It was so interesting to read your book and relate to a lot of the material you mention.’ Not only does she know the country well but her family tree goes back many generations there. ‘My ancestor Kommandant Jacobus Linde fought at the battle of Blouberg and supported General Janssens when he went into the hinterland to promote peace and harmony with the native tribes.’ Sybil has traced her roots back to Hans Jurgens Linde who arrived in the Cape in the service of the VOC [Dutch East India Company] in 1753. ‘Their descendants today farm in the Ceres district and have a huge enterprise exporting fruit.’

Sybil was intrigued with mention of Kydd attending the races in Cape Town in CONQUEST. ‘My ancestors bred race horses and my great Granny Annie would go riding every afternoon in her black riding habit!’

One of Sybil’s treasured possessions is Granny Annie’s recipe book, dated 1884, and she enjoys cooking many of the traditional dishes of the Cape. ‘The bobotie [a spicy minced meat dish topped with a savoury custard] you wrote about is to this day a very popular dish and I make it regularly when having visitors for a meal.’

In CONQUEST Renzi is offered a glass of liqueur after dinner by his host. ‘A Cape liqueur, made with the skin of the naartjie fruit …and named after Admiral van der Hum of the Dutch East India Company who did so admire it.’

Here is Great Granny Annie’s recipe for Van der Hum liqueur:

- 6 bottles brandy

8 small cups sugar (6 brown, 2 white)

30 cloves, 60 allspice, 2 sticks of cinnamon

1 wine glass of rum

1 small cup naartjie peel [a native citrus fruit, similar to a small mandarin]

½ nutmeg, grated

4 blaar foelie [blue figs]

This should be allowed to steep for a month or two in a cool place in a large stone jar and then decanted into glass bottles.

Cheers – or as they say in Afrikaans, Gesondheid!

Would you like to be a candidate for Reader of the Month? Just get in touch with a few sentences about your background and why you enjoy the Kydd series

Copyright notices

Janssens: By Jan Willem Pieneman (http://www.rijksmuseum.nl/collectie/SK-A-2219) [Public domain, Public domain or CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

The Naval Medals of England and most particularly during the Reign of George III

Posted on May 4, 2014 2 Comments

[To leave a comment or reply go to box at the end of the page]

Sim Comfort has built up a wonderfully eclectic treasure trove of coins, medals, paintings, swords and other naval items over many decades. He’s written and published a number of very fine books on the weapons and memorabilia of the Age of Sail (and is currently working on one on the Davison medals, to be published in 2017). I’m delighted to introduce his first Guest Blog, on the naval medals of England. Over to Sim…

I think it is fair to say that the British series the naval medal began with the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. Although it was Drake, Howard and Hawkins with their intrepid sea captains who doggedly attacked and weakened the great Spanish Armada, led by the Duke of Medina-Sidonia, it was a series of fierce gales that in the end dispersed the enemy fleet.

The Dangers Averted medal of 1589 which is attributed to Nicolas Hilliard (1537-1619), and found in gold, silver and copper was a cast and chased medal and has to be England’s first naval award medal, although the distribution was not exclusive to men of the sea. Previous to the Armada, Queen Elizabeth showed her favour to men who had provided an important service with the gift of a miniature portrait of herself or a valuable jewel. This practice was both costly and always took time for the miniature to be painted or the jewel to be manufactured. The introduction of the cast and chased or struck medal substantially reduced cost and speeded up availability of the gift.It was at Tilbury on 9 August 1588 where Elizabeth addressed her troops who were to defend her realm against the threat of a Spanish invasion. She wore half armour to show that she was willing to fight. Her words caught the moment:

- ‘I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king and a king of England too – and think foul scorn that Parma or any prince of Europe should dare to invade the borders of my realm.’

Elizabeth continued to say, ‘I know that already for your forwardness you have deserved rewards and crowns, and I assure you in the word of a prince you shall not fail of them.’

I think that it is with this promise to all who were before her, that she decided that if victory for her prevailed, that she would indeed reward those, whatever rank they may be, who brought that victory to being.

That the medal is ascribed to Hilliard is most fitting as he was Elizabeth’s principal miniaturist. The reverse features the bay tree which was believed to ward off lighting and disease.

The style of the Dangers Averted medal is as distinctively English as noted by Roy Strong in his two works regarding the English icon. That the medal is found in gold, silver and bronze makes me think that Elizabeth established the standard of distribution which appears to reflect the station of the recipient and was followed for the next 200 years or more. This bronze example (pictured) has undoubtedly been worn and served as a touch piece for many years. The medal was almost certainly awarded to a brave petty officer or seaman.

It is also important to note that with Elizabeth, the whole nature of England changed in that she would not involve her realm in Continental wars but would look at her domain as the sea and that it would be from the sea that England would gain her wealth through trade but also her protection with her sailors and fleet.

And so it was that with Elizabeth I the practice of awarding naval medals commenced, but it wasn’t always maintained by her successors. James I didn’t really distribute naval medals, however Charles I did and then Cromwell during the Commonwealth and during the reign of Charles II; fine naval medals were created, particularly to recognise achievement during the four great Dutch Wars. During this time, the Dutch too created astonishing naval medals to record the victories of Trump and de Ruyter. William and Mary also produced some very fine naval medals, but then with the reign of Queen Anne and the early Georges, the tradition largely lapsed.

It was King George III who brought it back and in a fashion which not only meant medals were awarded by the King, but inspired private individuals, who took it upon themselves to also recognise achievements at sea by awarding naval medals.

Following Admiral Earl Howe’s defeat of the French fleet on the Glorious 1st of June, 1794 when Howe’s flagship, Queen Charlotte, arrived in Portsmouth, the King came on board and presented Howe with a long gold chain as a mark of achievement. The King then ordered that large gold medals, that would be suspended by a blue and white ribbon from the neck, be granted to victorious flag officers. A small gold medal, also suspended from a blue and white ribbon and worn at the uniform buttonhole, was awarded to victorious captains.

Although this practice was greatly admired by the recipient officers, it was also fraught with problems, particularly as Howe nominated only certain of his captains of his fleet to receive the naval small gold medal. Those he didn’t select were left with the taint of ‘lack of zeal.’Another facet for discontent was the view to save money by being restrictive in terms of who qualified for a naval gold medal. An example being that Captain Hardy of the brig Mutine at the Nile, received no medal because Mutine wasn’t a ship of the line. Lieutenant Cuthbert of Majestic, who fought the ship right through the night at the Nile following the death of his captain, George Westcott in the first 15 minutes of the action, and probably accounted for more enemy ships than any other at the Nile, didn’t receive the medal because Cuthbert wasn’t a captain.

Captain Hardy’s Trafalgar naval small gold was auctioned by Christie’s in 2005 and made over £260,000.The situation was also made difficult because the government was involved with the decision as to who would receive a medal. Nelson and his captains received no medal for their victory at Copenhagen in 1801 and Gambier also received no medal for himself or his captains when Copenhagen was again attacked in 1807. As Nelson mentioned, ‘our brothers the Danes’, reflected accurately on the national sentiment. The Danish actions were necessary, but not to be celebrated.

Although several English medallists during the period 1793 – 1815 produced naval medals as commercial ventures to sell to both the collecting public and to officers and men from returning victorious fleets, there are two very important private ventures from the period which weren’t based on commercial gain, but just as a mark of respect to Britain’s brave seamen.

Alexander Davison was a very important personal friend of Nelson’s and was the prize agent for Nelson’s fleet at the victory at the Nile, 1 August 1798. Such was Nelson’s success, and one that many today consider this his finest victory even eclipsing Trafalgar, that Davison asked Matthew Boulton to produce a medal in gold to go to Nelson and his captains, in silver to his senior ship’s officers, bronze gilt to petty officers and bronze for the men. A fine bronze gilt Davison Nile medal that has been engraved, cased and glazed will bring between £3,000 and £5,000 in auction.Nelson was thrilled by this gesture and kept a supply of bronze medals with him which he presented as a token of regard during his subsequent travels. Some of the men of the Nile, having seen how good the gilt examples looked, had their medals gilded and named and these medals are now highly sought after by collectors.

Davison used the Crown’s scheme for distribution of his medal, so the captain and men of the brig Mutine didn’t receive the medal. One remembers that when the Davison gold medals for captains arrived with Nelson to distribute, Hardy was with Nelson and Nelson gave to Hardy the medal intended for Captain Westcott of Majestic ‘because he won’t be needing it now!’ said Nelson of the dead Westcott. The gold Westcott / Hardy medal was auctioned by Christie’s in 2005 and made over £80,000.

Matthew Boulton was himself struck by the generosity of Davison and with the victory of Nelson’s fleet at Trafalgar, had a medal in tin struck at his own expense and distributed to the men before the mast. Boulton’s reckoning was that the officers would receive sufficient rewards; it was the men who needed special attention. His gift wasn’t always received well though as the men thought their tin medals inferior to the bronze medals of the Nile, and some threw them overboard.

Having said that, many men fully appreciated the importance of the gift and had their medals engraved, cased and glazed and when found today, fetch between £3,000 to £5,000.

There is also a large tin medal which is believed to have been presented by Davison to just the men of Victory. Nothing certain is known, but today it is generally attributed to Davison and the medal fetches between £2,000 and £3,000 in auction.

Although both the Davison Nile and Boulton Trafalgar medals are deemed ‘unofficial’ awards, they both gained the approval from the King and the Admiralty for their distribution to the men of the victorious fleets. Nelson’s effigy in Westminster Abbey shows the admiral wearing a bronze gilt Davison Nile medal.

There followed in 1848 the first Naval General Service Medal which was again fraught with difficulties. The general feeling was that the Crown should recognise the efforts made by the officers and men who fought at sea during the two great French wars. The same concern went to the Army. As a result the NGS and MGS were awarded to men still alive in 1848, who could prove that they took part in a naval or military victory.If one considers that nearly 20,000 men fought at Trafalgar and only 1,250 NGS medals were awarded with the Trafalgar clasp, one can imagine the discontent felt by many families. Further, for an action to be recognised, an officer had to have been promoted because of the action, which left many fine actions without recognition. Although Nelson’s victory at Copenhagen in 1801 was recognised with a clasp, Gambier’s in 1807 wasn’t. And worst of all – Admiral Sir George Cockburn, who had been First Sea Lord in the 1840s; his capture of Washington was not recognised, and Cockburn was not at all pleased because this was the capture of the only enemy capital during the long wars, but again politics meant that one shouldn’t celebrate such a victory over the Americans.

Today, an NGS with Trafalgar clasp will easily make £5,000 in auction, and medals with rare clasps may fetch four or five times that amount.

One should also mention the establishment of the Lloyd’s Patriotic Fund in 1803 which awarded swords and vases of honour to such men as they deemed worthy. Perhaps more important was the care and support of the wounded and the provision of annuities to the dependants of seamen killed during the Napoleonic War. The fund still exists and continues to support men and women casualties while serving with Her Majesty’s Forces.

Sim’s website

See also: Sim’s Treasures

BookPick: Lord Nelson’s Swords

Image credits:

Dangers Averted, Boulton Trafalgar: Sim Comfort Collection

NGS, Hardy’s Trafalgar medal: Christie’s auction house, London

BookPick: The Sloop of War 1650-1763

Posted on May 1, 2014 1 Comment

[To leave a comment or reply go to box at the end of the page]

Ian McLaughlan’s splendid book is the first study in depth of the Royal Navy’s vital, but largely ignored small craft – the sloop of war, like Kydd’s beloved Teazer. In the Age of Sail they were built in huge numbers and in far greater variety than the more regulated major warships, so they present a challenge to any historian attempting a coherent design history.

This book ably charts the development of the ancillary types, variously described in the 17th century as sloops, ketches, brigantines, advice boats and even yachts, as they coalesce into the single 18th-century category of sloop of war. In this era they were generally two-masted, although they set a bewildering variety of sail plans from them.

The author traces their origins to open boats, like those carried by Basque whalers, shows how developments in Europe influenced English craft, and homes in on the relationship between rigs, hull-form and the duties they were designed to undertake. Visual documentation is scanty, but this book draws together a unique collection of rare and unseen images, coupled with the author’s own reconstructions in line drawings and watercolour sketches to provide convincing depictions of the appearance of these vessels. A half dozen detailed appendices supplement the main text.

By tackling some of the most obscure questions about the early history of small-boat rigs, this book will be of interest to historians of coastal sail, practical yachtsmen, warship enthusiasts and Old Salts in general.

I look forward to perhaps a sequel that addresses that changes in sloop design that came after the end of the Seven Years’ War.

Published by Seaforth, 2014 ISBN 978 1 84832 187 8

Countdown to CARIBBEE!

Posted on April 26, 2014 2 Comments

‘A thumping good read – a wonderful platform for Stockwin’s powers of description, his mastery of the nautical environment and talent for sketching in a totally credible world…His easy-going, fluid storytelling totally immerses the reader.’ – Warships magazine on CARIBBEE

The UK paperback edition of CARIBBEE is published by Hodder & Stoughton on May 8.

The UK paperback edition of CARIBBEE is published by Hodder & Stoughton on May 8.

Today marks the start of COUNTDOWN TO CARIBBEE, a special focus on CARIBBEE on Facebook and Twitter

As well as snippets of Caribbean lore and research photographs from my personal album there’s a chance to win one of six paperbacks of the book. One lucky winner will also receive a Caribbean recipe book, a packet of thyme seeds (a fave ingredient in that cuisine) and a bound uncorrected proof copy of the book! (These are prized collectors items as they are printed in very small numbers.)

To go into the hat, email julian@julianstockwin.com with ‘Count me in’ as the subject line. Please include your name and address in the body of the email.

A draw of all entries will be held on May 8 and the winners contacted by email.

Tenacious: the hunt for Napoleon’s fleet

Posted on April 23, 2014 21 Comments

The sixth book in the series is TENACIOUS. Kydd is in Halifax enjoying the recognition and favour of his fellow officers when his ship Tenacious is summoned to join Nelson’s taskforce on an urgent reconnaissance mission.

One reviewer said of this book:

- ‘More sea adventures of Thomas Kydd, this time meeting Horatio Nelson and taking part in the cataclysmic Battle of the Nile, where an outgunned British fleet takes on the might of ascendant France off the coast of Egypt in a blazing, history-changing, battle. The historical research is flawless, the battle scenes are horrific, Kydd’s efforts to become a gentleman are heart-rending, and the unending philosophical struggles of Nicholas Renzi are capped by a mortal sickness. I am totally hooked on this delightful series. It’s a 5!’

(I rather liked that review…)

I’m sometimes asked had my original conception of Tom and Renzi altered much by the time I’d got the first half dozen or so books completed.Yes, in some ways it had. Probably the main change was in the relationship between Kydd and Renzi. At first I thought Renzi would just be a useful foil to Kydd and as a vehicle for passing on elements of refinement on Kydd’s road to becoming a gentleman – but as successive books were written Renzi took on a new importance. Not only did he become a pivotal character in his own right but he needed Kydd as much as Kydd needed him.

The historical backdrop

In terms of material for TENACIOUS I was spoiled for choice. It was a time of titanic global stakes. If the Nile or Acre had been lost we would have seen Napoleon dominating a world which would have been very different today. And it was a time of deeds so incredible that they may seem like fantasy but are not – Nelson personally saving the king and queen of Naples at cutlass point, Minorca taken without the loss of a single man – and above all, the astonishing but little-known fact that Napoleon was first defeated on land not by a great army but a rag-tag bunch of sailors commanded by a maverick Royal Navy captain.

Minorca

One of the highlights of my location research was Minorca. The charming island boasts a magnificent harbour, one of the finest in the world – nearly four miles long and a maximum width of close to half a mile.

The British occupied Minorca at three different periods in history, the last being from 1798 to 1802. It was interesting to compare it to Gibraltar, which admittedly was very strategic, being at the mouth of the Mediterranean, but because the Rock stuns the winds, it was not a very good harbour for a fleet. Minorca, on the other hand, was – and is – a fine sheltered harbour, certainly more in the geographic centre of things in the eighteenth century.

Naples

Ah, Naples. Glorious Naples! How I would have loved to have been there when Nelson sailed in to the magnificent bay with his battered ship and two other vessels of his squadron to be greeted by hundreds of boats full of joyous passengers – and the king of Naples in the royal barge. The feting of the heroes of the Nile didn’t stop there. There were parties – and a grand reception at which Emma Hamilton performed her famous ‘attitudes’. It’s not known when Emma and Nelson first became actual lovers, but it’s clear that Naples was a turning point for them…

In the book I decided to have Sir William Hamilton, a classical scholar and amateur scientist of renown, invite Kydd and Renzi to join him on a visit to Herculaneum, promising to take in Vesuvius on the way. One hot morning Kathy and I followed in their footsteps up to the fabled volcano and peered through sulphurous mists down into the hellish depths of the crater.

Local research

Well, closer to home, the Admiralty Hydrographic Office at Taunton, Somerset, proved most helpful allowing me access to charts of time and one of the actual maps used in the siege. I cherish maps and charts and could have spent the whole day there!

The book’s dedication

It was one of those happy coincidences that TENACIOUS was published in 2005, the year of the bicentenary celebrations of Nelson’s great victory of Trafalgar. I knew there could only be one dedication for my book:

- ‘There is but one Nelson.’ –Lord St Vincent

When I began the Kydd series, as I plotted out the general content of each book, I knew my central character Thomas Kydd would meet Nelson at some time. No writer in this genre can tell of the stirring events in the great age of fighting sail without being aware of Nelson at the centre. But it was not Trafalgar that I selected for this first meeting; it was at the Battle of the Nile – in my mind Nelson’s finest hour.

In the course of my research for this book my admiration for Nelson – which was already considerable – increased immeasurably. He was undoubtedly a true genius as a leader of men, but he also had a great humanity and such respect for the lower deck that he insisted on adding a pair of common seamen to his knightly coat of arms.

Copyright notices

Battle of the Nile: By George Arnald [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons;

Emma Hamilton: Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice