Ask BigJules: Double Helping!

Posted on November 14, 2013 6 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

The first question comes from David Slinn who wants to know the origin of the term ‘tarpaulin officers’ :

- There weren’t many in the Georgian navy who made the hard journey from before the mast to officer on the quarterdeck – just a few hundred in the whole of the period of the French wars, Tom Kydd included! In nearly all cases these were hard men from humble backgrounds who had no truck with fancy manners and fine clothes like those who entered the officer class the easy way – as midshipmen with family wealth behind them. Tarpaulin officers were known as such because in foul weather like the seamen they wore gear made of tarpaulin, canvas waterproofed with tar. It was very practical attire in grievous cold and wet but well-bred officers looked on the practice with disdain as the clothing smelled pretty tarry and the reek of the tarpaulin officer lingered on in the ward room.

The second question was asked by Jeff Souder. ‘Is there a maritime origin for the phrase “lower the boom”?

- Today, in colloquial speech, lowering the boom means abruptly stopping someone from doing something. A good case can be made for salty derivation. A boom is a long spar, used for example, to extend the foot of a particular sail. When a ship makes port, the boom is lowered (to take the strain off the standing rigging). The ship has stopped, her voyage is over.

- Another explanation I once came across is that in the days of pirates an annoying crew member could be got rid of by making sure he was standing near the boom, then loosening the lines. The boom would swing, crash into the unsuspecting victim – and knock him overboard.

Do send in your questions for Ask BigJules!

Copyright notices

Image: Thomas Rowlandson [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

BookPicks for Christmas

Posted on November 12, 2013 3 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

Books make great Christmas gifts and I’ve chosen twelve to recommend for Santa’s sack. Some classics, some discoveries – and all have a maritime connection of some kind…

Broadsides BroadsidesBy James Davey and Richard Johns, Seaforth The Royal Navy during the second half of the eighteenth century through the lens of contemporary caricature. Witty and perceptive! [ Buy ] |

Under a Yellow Sky Under a Yellow SkyBy Simon J Hall, Whittles Publishing A lively memoir written of the time when the British merchant fleet was still one of the largest in the world – and the Red Ensign a common sight. [ Buy ] |

Courage on our Coasts Courage on our CoastsBy Nigel Millard, Conway Commencing on the Isle of Man – the birthplace of the RNLI – a clockwise circumnavigation of the British and Irish coasts. Stunning photography! |

Nelson, Navy & Nation Nelson, Navy & NationEdited by Quintin Colville & James Davey, Conway The Royal Navy and the British People 1688-1815. Superbly illustrated. |

British Naval Swords & Swordsmanship British Naval Swords & SwordsmanshipBy John McGrath and Mark Barton, Seaforth A fascinating look at the sword – not just as a sought-after collector’s piece but its position in the wider social and historical context. |

The Conquest of the Ocean by Brian Lavery The Conquest of the Ocean by Brian LaveryBy Brian Lavery, Dorling Kindersley A gloriously illustrated account of 5000 years of seafaring history. [ Buy ] |

JackSpeak JackSpeakBy Rick Jolly, Conway The humourous and colourful slang of the Senior Service. A delightful book to dip into! |

Nelson’s Navy Nelson’s NavyBy Brian Lavery, Conway Reprinted many times, this is must be the most comprehensive one-volume overview of Britain’s navy during the Napoleonic wars. Highly recommended. |

Hunter Killers Hunter KillersBy Iain Ballantyne, Orion The incredible true story of the Cold War beneath the waves. Now told! |

The Sailors Word Book The Sailors Word BookBy William Smyth, Cambridge University Press An indispensable guide to nineteenth-century nautical vocabulary. |

Turner and the Sea Turner and the SeaBy Christine Riding and Richard Jones, Thames & Hudson Throwing new light on the seascapes of one of the foremost figures of British and European art. A coffee table book to treasure! |

Broke of the Shannon and the War 1812 Broke of the Shannon and the War 1812By Tim Voelcker, Seaforth His victory over Chesapeake had far-reaching consequences. A timely update in the bicentenary year of his victory. [ Buy ] |

And if you’re looking for a specific Signed First Edition Kydd title I still have a few available. Email julian@julianstockwin.com for details and prices. (Kydd Club members are entitled to a 10% discount on all purchases.) I’m happy to add a personal Christmas message. To ensure delivery in time for Christmas the deadline for orders is November 30. Don’t delay to avoid disappointment!

CARIBBEE Signings

Posted on November 12, 2013 10 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

It’s always an enjoyable time for me when a new book comes out and I travel around various bookstores meeting readers

If you didn’t manage to catch me at one of the earlier signings here’s another two coming up soon:

- On Saturday November 23 I’ll be at Torbay Bookshop at 10:30

The Torbay Bookshop

7 Torquay Road

Paignton

Devon

TQ3 3DU

Tel: 01803 522011 - And on Thursday November 28 I’ll be at Waterstones Drake Circus, 3 pm

Waterstones

1 Charles St

Plymouth

PL1 1EA

Tel: 0843 290 8551

See you there!

The Cold War Under the Sea

Posted on November 8, 2013 17 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

I must confess to a special interest in ‘Hunter Killers’ by Iain Ballantyne; all of my time in the Navy was during the Cold War. I’ve found no other book that delves so comprehensively into the underwater battle space during those tense years – and I’m delighted to welcome Iain as my third Guest Blogger.

Last of the Cold War warriors: the British nuclear-powered attack submarine HMS Sceptre

Photo: Nigel Andrews

‘…there are two ways of dying in the circumstances in which we are placed…The first is to be crushed; the second is to die of suffocation. I do not speak of the possibility of dying of hunger, for the supply of provisions in the Nautilus will certainly last longer than we shall. Let us then calculate our chances.’ – Captain Nemo, ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.’

Published in 1870, this was a ground–breaking novel that depicted havoc caused across the oceans by a revolutionary type of submarine.

It was fast and could inflict instantaneous destruction on surface vessels – it struck without warning and then was gone again. It was a type of fighting vessel that did not really become reality until the advent of nuclear–powered submarines in the 1950s.

‘Of all the branches of men in the forces, there is none which shows more devotion and faces grimmer perils than the submariners.’

The face–off between the West and the Soviet Union was by then threatening to burn white hot. During the so–called Cold War there were two competitions – one for command of outer space and the other for control of inner space.

We know plenty about the former and of the latter, hardly anything at all.

The more crucial competition was the hard fought contest waged by the USA, Britain and USSR across a darkly secret maritime battle space. For nearly five decades Humanity’s fate was in the hands of men who silently, secretly and without fanfare or adulation sailed in the silent deep of the world’s oceans. The Cold War submariners.

Year after year they took their vessels out on deployment, disappearing beneath the surface of the sea for weeks, if not months, at a time. Between the last time they saw their homeland and the next, babies were born and loved ones died. Wars might be fought or peace and goodwill reign. Deep in the oceans, throughout every personal tragedy and triumph, each world–shaping event, they hovered, unseen and ignored by the majority of Mankind, on the edge of the abyss.

Not only was their deadly theatre of the Cold War literally hidden from the eyes of all except them, the secrecy imposed on both sides was almost all encompassing. Very few shafts of light fell on what really happened and, even to this day, it remains mostly in the shadows.

The campaign waged beneath the waves by British submariners was the most dangerous of plays in the East–West confrontation (between the late 1940s and 1991) and the Royal Navy’s men evolved into its deadliest practitioners.

On long–range missions in diesel boats, fresh water could be in short supply and food run short, with the submariners’ mental and physical health possibly deteriorating – but somehow they endured. In the nuclear–powered vessels the submariners had all the water and oxygen they needed – sheer luxury compared to the early Cold War ‘dirty boat’ diesels.

In Cold War submarines the mission invariably came before the man. For example, in the UK’s ballistic missile boats – the Polaris ‘bombers’ – surfacing to send a mortally sick sailor ashore to hospital could not happen. For it would endanger the primary mission of staying hidden and undetected for an entire patrol. The poorly submariner would have to take his chances. If he expired his corpse would be stored in a refrigerator compartment.

Out there, in the vast ocean, responsibility for the safety of nuclear–propelled submarines and their crews, often manoeuvring in rather close proximity – and occasionally coming to grief – fell on the broad shoulders of a few remarkable men.

The experiences of submarine captains recounted in “Hunter Killers” are unique they but they also serve to represent the broader tale.

The same could be said of the stories told by a small supporting cast of ratings whose fate the officers decided. They are also representatives of an amazing breed of men, all engaged in what was an expansive, yet deeply personal, drama.

A Polaris missile is launched from the nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine HMS Renown

Photo: US DoD

At times such men held more destructive power in their hands than had ever been unleashed on the planet. The Cold War undersea warriors in the attack submarines – the undersea fighter jets of the contest – often had to take split– second decisions. Upon them depended the lives of not only their own sailors but also those of millions living ashore in complete ignorance of the high stakes poker game unfolding at sea.

Today we grapple with different life and death matters on the world stage in a radically changed society. We forget how turbulent, how terrifying and exciting it could sometimes be to live back then. Nowhere was the cutting edge of science more crucial than in the face–off beneath the waves. Gaining knowledge of each other’s technology was one of the key prizes. Espionage lay at the heart of submariners’ activities – whether striving to record the distinctive sound signatures of Soviet submarines and surface ships, or eavesdropping on, and covertly observing, missile tests and other military and naval activities.

To know an enemy’s vulnerabilities – and capabilities – without him realising you had gained that insight was the ultimate. It awarded the possessor a killer edge. Nobody was a more formidable deep cover agent than the Royal Navy submariner of the Cold War.

It is therefore about time we knew at least who some of them were, in order to understand what they all did, or at least as much as secrecy rules will permit us to reveal. In that way we can at last understand what the rest of us actually lived through. For without this story there are pieces of the Cold War jigsaw missing, the truth obscured.

Winston Churchill paid this tribute: ‘Of all the branches of men in the forces, there is none which shows more devotion and faces grimmer perils than the submariners.’

The mindset in the Royal Navy during the Cold War was that the Submarine Service was the pre–eminent arm. For the most serious threat to the existence of the West at all levels came from beneath the surface of the sea.

There were Soviet nuclear missile submarines (SSBNs) ready to wipe out all civilisation, not forgetting guided missile submarines and attack boats that could, in time of war, cut supply lines across the Atlantic, starving NATO of troop reinforcements. They could also deny the civilian population food, energy and many other goods considered essential to daily life.

The Russians had hundreds of submarines of all varieties and nothing that floated on the surface of the sea – whether warship or merchant vessel – was safe from them. The only answer was for NATO to field better hunter–killer boats to hunt the enemy down and to meet burgeoning Soviet SSBN destructive power with Royal Navy ‘bombers’ and US Navy ‘boomers’.

Unable to match Soviet numbers, the key to success was in the fine margins of tactical success. And that is where the British submariners proved their worth. The Royal Navy may not have fielded the most submarines during the East–West confrontation, but it sent them into the danger zones where it mattered.

The ultimate tribute to the Royal Navy’s operators perhaps came from the late Tom Clancy: ‘While everyone deeply respects the Americans with their technologically and numerically superior submarine force, they all quietly fear the British.’ Clancy went on: ‘Note that I use the word fear. Not just respect. Not just awe. But real fear at what a British submarine, with one of their superbly qualified captains at the helm, might be capable of doing.’

For a chance to win a copy of ‘Hunter Killers’ – email julian@julianstockwin.com and name one of the other books Iain Ballantyne has written. Please include your full postal address. Deadline for entries: November 15. The first two correct entries drawn will be the winners and will be notified by email.

King Sugar

Posted on November 5, 2013 7 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

The two of my books set in the Caribbean – SEAFLOWER and CARIBBEE – cannot help but touch on King Sugar. Renzi’s brother is a plantation owner in Jamaica and as well as this family connection, England had vital economic and strategic considerations stemming from the crop.

In the late eighteenth century a diligent housewife following the latest cook-book from Hannah Glasse would find in her recipe for a nice cake ‘in the Spanish style’ a requirement for a whole 3 lbs of sugar, and if she was making marmalade it would have to be a pound of sugar for every 4 oranges. The same lady would need to find somewhere between 12 and 16 lbs of sugar for every 1 lb of tea. To say that Britain had a sweet tooth was a bit of an understatement! Some parishes even had a definition of poverty as the inability to buy sugar to go with your tea – second hand tea, of course.Starting in earnest in the late seventeenth century, Caribbean plantations began producing jogarree, or unrefined sugar, until, by the eighteenth century, a gigantic river of wealth began flowing across the Atlantic. It didn’t escape the British government that this fount of silver should be well guarded, and of course the French had similar views – and the stage was set for the most fought-over piece of empire to date.

Napoleon Bonaparte did all he could to wrench it away from John Bull – Trafalgar was really about sending Villeneuve with a great battle-fleet to take our sugar islands. They were only saved by the French admiral hearing Nelson was on his heels, causing him to flee back to France.

CARIBBEE is about another insidious plot to bring downfall and ruin to England’s sugar interests that nearly worked…

Growing sugar cane was labour intensive and yes, there was slavery involved. Some ask why this wasn’t abolished at the same time as the trade in slaves. The obvious answer is that if one country freed their slaves and started paying them good wages it would put them out of business in the face of others with no labour costs.

The poet Cowper put it in blunter terms: ‘I pity them greatly, but I must keep mum; For how could we do without sugar and rum?’

Ironically, at about the same time as slaves won their freedom an industrial process was invented in Europe to extract sugar from sugar-beet and the bottom dropped out of the Caribbean sugar market leaving them perhaps worse off.

‘I pity them greatly, but I must keep mum; For how could we do without sugar and rum?’

But in its heyday sugar was king. There were risks, however; a hurricane flattening the crop just before harvest; a slave rebellion and destruction of crops and machinery; a younger son sent out to manage the estate dropping dead of yellow fever in three days. Privateers capturing an entire cargo at sea.

And of course getting caught in the wars that raged around. If an island was taken it meant confiscation and instant ruin but if a French one was taken that was one less rival. Lucia was taken and re-taken during the wars a total of some 14 times! In the end however, mainly due to command of the seas, the British got the lot.So what was involved in this great enterprise? When the crop was ready for harvest, it was cut and sent to the mills where it went through great rollers, yielding the sugar juice. It then went to the boiling house where lime was added and it came out as a thick syrup. This was tapped off into hogsheads with holes in the bottom. This let out the liquid, molasses, to become rum and what was left was crude crystallised sugar.

When it arrived in England this was taken a sugar-house (Bristol had many) where it was clarified with egg-white and vinegar then cattle blood was added.

The end product was the sugar loaf, from which pieces of sugar were ‘nipped’ off and granulated. Cubed sugars were not introduced until the late 19th century.

CARIBBEE is out now

Copyright notices

Sugar loaf: By Petr Adam Dohnálek (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 cz (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/cz/deed.en)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons; Cut sugar cane: By Rufino Uribe (caña de azúcar) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

‘The Best Job in the World’: A Guide Aboard Victory

Posted on November 3, 2013 26 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

HMS VICTORY is among the most famous ships in history; the only surviving warship that fought in the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary War and the Napoleonic wars. She served as Lord Nelson’s flagship at the decisive Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Now preserved for future generations in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard she’s a must-see for all those with an interest in history and the Royal Navy. I must have toured over this iconic ship 20 times, and I was privileged to have been given special access during the research for my book VICTORY. For this second Guest Blog Post I’m delighted to introduce one of her current guides, Chris Revell, who says he has the ‘best job in the world.’

From the age of ten I was always fascinated with the Napoleonic wars and purchased any books on the subject when I could – it’s now built up into quite a collection!

I became a boy soldier and served as a trooper with the Junior Tradesman’s Regiment at Rhyl, North Wales until I went to West Germany and joined my parent regiment 2nd Royal Tank Regiment based in Munster.

I left the army and joined the London Fire Brigade which I loved – a lot of ladder work, ropes and routine based on the navy structure.

When I moved to Bognor Regis I decided to join the police. In 1979 I transferred to the Sussex Police and completed a further 28 years pounding the beat. On retiring in 2007 I looked for vacancies at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard with a view to gaining employment in HMS Victory. Sadly there were no vacancies but HMS Warrior was looking for a quartermaster. So for the next six years I was employed on a wonderful iron warship whilst biding my time for a vacancy on HMS Victory.

In February of this year HMS Victory was advertising for guides so I applied and the silly buggers took me on! I work from March to the end of October as a seasonal worker doing full time hours. This consists of standing at various points talking to the public about Victory, the personalities, the battles, life for the officers and crew – and the Georgian period. I also conduct tours around the ship, mainly for those attending dinners aboard; these have included admirals and foreign dignitaries, sometimes quite daunting!

From November we go onto tours only. These tours take you all the way round the ship and last about 50 minutes. We have a basic script to learn but are encouraged to make it our own and bring the ship alive.

My day begins at 0900 when I change into uniform in the building directly overlooking the bow of Victory. I then chew the fat with my colleagues, male and female of all ages. After doing a sweep of the ship to check that the route is clear, all ropes are in place, signs are out and fire escapes in order, we open the ship at 1000.

We are assigned a point within the ship which also includes the entrance and the exit and await the deluge of happy visitors.

My favourite point is the Middle Gun Deck right next to the original 24 pounder gun and the Brody stove. I enjoy explaining how the gun deck must have been in the midst of battle, what the crew ate and how the Battle of Trafalgar unfolded.

I love the great cabin, talking about the great man whilst standing in his day cabin next to the round table where it is reported he wrote his last prayer; it still makes the hairs go up on the back of my neck.

We stand at a point for up to three hours then take a tea break, move onto another point, have another tea break and then the final point till the close of the ship at 1730. The day goes so quickly due to the amount of questions you get asked, and as we say we never get a silly question – but we do have a laugh!

We have been particularly busy this summer with an average of 3000 per day coming onto the ship, this includes a lot of parties from all over the world. We are now at about 1000 a day.

HMS Victory is undergoing a 20 year programme of conservation and repair work so that she will be around for another 250 years to educate and amaze the public. One of the changes that I’m excited about will be in the Great Cabin and Captain Hardy’s Cabin. The bulkheads etc in these two locations are stained a dark brown, which was carried out by the Victorians. Hopefully next year these two cabins will be restored to their original colours of white and pale blue.

—

HMS Victory

—

For a chance to win a signed copy of my book VICTORY leave a comment below. We’ll choose a winner at random. Deadline: November 8

An Epoch of Life and Vigour

Posted on November 1, 2013 5 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

Thomas Kydd was born in the Georgian Age, into a family whose livelihood depended on wig-making, a trade that would gradually diminish in importance over the coming years.

The Georgian Age, an epoch full of life and vigour, is variously defined (but most generally take it from the reign of George 1 in 1714, to the ascension of Queen Victoria in 1837). It was certainly a time of great change and huge contrasts. During the Georgian period we can point to what was probably the most graceful, leisured and cultivated time that England has known but also to the tragic consequences of the Enclosure Acts, the appalling conditions of factory life, the harsh criminal laws, the incidence of drunkenness, squalor and disease.

The early Georgians were natural, spontaneous, and straightforward. The stiff upper lip had not yet been built into the character of the English. That would come as the Georgian era morphed into the Victorian Age, partly due to the evangelical movement, partly as a reaction against the unsettling of the traditional order by industrialisation.

As the eighteenth century progressed ordinary people enjoyed a far better standard of living than ever before, and the opening up of road communications increased optimism and the feeling of attaining a new level of civilisation.

Between 1700 and 1800 the population doubled (to 8.8 million in England and Wales), many great newspapers were founded, and the middle classes – merchants and small shopkeepers, doctors, lawyers, the new landowners – came to feel more sure of their identity. Exotic influences sprang from a growing internationalism brought about by the Grand Tour and the greater ease of foreign travel, by the trading of the East India Company and other merchants, and by the voyages of explorers like Captain James Cook. These influences made themselves felt in literature, architecture and the sciences.

A steady accumulation of wealth continued throughout the Georgian period. In 1783, it was estimated that there were 28 peers with land in excess of 100,000 acres. The Industrial Revolution had its birth under the Georges but did not reach maturity until Victoria’s time.

London, ‘the Great Wen’, grew remorselessly during the Georgian era. In 1763 James Boswell observed that ‘one end of London is like a different country from the other in look and manners.’ While the rich relocated among the fashionable new squares and terraces of the West End, and the ‘middling’ classes built homes in outlying areas such as Blackheath, Putney and Kew, the poor crammed into the vacated districts on the fringes of the old City. The teeming East End ‘rookeries’ were vividly portrayed by Hogarth’s grim engravings.

Although there was a large-scale movement of workers from the countryside to London and other cities, even in 1801 78% of the population of England and Wales still lived in the country. (A fifty-fifty distribution of country vs. city dwellers was not reached until 1851.)

London’s population had topped the million mark by 1810, becoming the biggest city in the world…

Copyright notices

Leicester Square: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Hogarth print: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

The Kydd Kit: Spread the Word!

Posted on October 29, 2013 9 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

Sorry – SOLD OUT !

Would you like to help ‘spread the word’ about the Kydd series? We’ve put together a great KYDD Kit – a special selection of Stockwin memorabilia: some to keep for yourself, others to hand out to ‘spread the word.’ You can pass them on to friends, bookshops, your local library – wherever you’d like to recommend the adventures of Tom Kydd.

This free KYDD Kit includes postcards, bookmarks, an author photograph, signed bookplates, a mystery item – and a great Union Jack Tote! There is a small charge for postage.

The Quarterdeck Interview

Posted on October 27, 2013 6 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

[ This interview is from the October issue of ‘Quarterdeck’ magazine ]

During your formative early years was reading an important part of your life?

Oh, yes. My mother introduced me to the joys of the public library when I was quite small and it was always a huge treat to go there and borrow books, especially when I had my very own junior library card! I have such fond memories of my first library that when I returned to the UK after many years abroad I searched it out, hoping it was still there. Sadly, it had been morphed into a council building, but amazingly, ‘Library’ is still emblazoned above the door. As a boy I had a pretty eclectic range of interests but anything to do with the sea was always there at the top of the list. When I joined the Royal Navy I had some treasured copies of Forester’s Hornblower books that I reread many times; I was actually at sea when he died and I was devastated that his wonderful stories would be no more.

You trained as a shipwright and I once heard you say you would feel quite at home in one of Kydd’s ships, adze and whipsaw in hand. Can you tell us a bit more about that period in your life?

I went to a prestigious English grammar school but didn’t do particularly well scholastically, spending my time watching the low grey shapes on the horizon and dreaming about the sea. I think my father had other ambitions for me but from an early age I always knew I wanted to join the Navy, and signed up for the saltiest branch of all. I trained as a shipwright in the Navy (a four-year apprenticeship), and am one of the not that many remaining chippies qualified to work on wooden ships of the big sort.

My ‘graduation’ project was to work on a naval whaler, a two-masted wooden boat, similar to Bligh’s little launch. With it I was able to put into practice all the skills of the craft, passed on to me in a long unbroken line down the ages. You never know when you’ll be called upon to sny and fay with a wrain bolt to three curvatures simultaneously…

At first glance, such skills may may seem obsolete for the modern navy but when I was involved in the Melbourne/Voyager tragedy it was we shipwrights who were vital in damage control and preventing further deaths. I was actually out with the seaboats that night keeping them afloat while pulling in survivors.

When I left the navy I worked for a time at Purdon & Featherstone (established in 1853, and sadly no longer in existence) in Hobart, Tasmania. This was one of the major slip yards for wooden boat construction and repair in the state. Some beautiful traditional wooden boats passed through there.

Has your experience as a shipwright influenced your writing?

I think all life’s experiences must play a part in the creation of a novel. Certainly many of the sights I saw on my voyages around the world are brought to bear in my writing.

As to my training as a shipwright – this gave me confidence to write several episodes in the series where there is quite some detail about Georgian naval dockyards.

I can also look at ship models – especially the scratch built ones – with an appreciative eye and because they are on a small scale I sometimes am reminded of things that I later bring to bear in my writing.

CARIBBEE is your fourteenth Thomas Kydd novel. Over the previous books, your plots have been closely tied to historical events. How do you approach development of your storylines which wrap around actual history?

To me, it is crucial to remain true to the historical record. I believe it would be a great disservice to both modern readers and those who lived in days gone by not to do so. I spend a great deal of time doing research before I write. Having said that, there are occasions when I believe it is permissible to vary, not the sequence of events, but time alone – for the sake of the story. I’ll give you an example, in KYDD, my first book, Tom finds himself at sea in the old Duke William pretty quickly. It would have been a pretty boring read to just have him aboard, swinging to anchor for weeks, as they sometimes did.

Do you ever encounter writers block? If so, how do you work through it?

Fortunately I’m writing about such a fascinating period in history that I’m usually carried along by the momentum of those glorious times. The Georgians were in many ways much larger than life than most of us today; they had a wonderful phrase, ‘bottom’ to describe the almost superhuman courage often found in tight corners.

I guess, also, that because I do very detailed research and planning before I set pen to paper I know where the story is going and am not bogged down by false starts. If I do need to fine-tune some plot point I find that being able to walk/talk with Kathy along the banks of the nearby River Erme is a great boon. Mind you, once we just couldn’t seem to find a solution and it took six hours of ‘pacing’ before the answer finally revealed itself.

Did you and Kathy get to return to the West Indies for CARIBBEE?

Sadly, no. It’s a long way from Devon, and quite an expensive trip! However we did have over three weeks there on location research for SEAFLOWER, and I knew Kydd would be returning there at some point in his career. We took hundreds of photographs and extensive notes so I wasn’t short of material for CARIBBEE. I also have a full set of Navy electronic navigation charts of any region which I have to hand as I write.

How much does music mean in your life?

I find great joy in music. Along with reading and good food it’s one of life’s great pleasures.

Have you any skill at music? Do you play an instrument?

Sadly, although I have a good musical ear, I am an amateur in terms of skill. In the Navy I played a horn in the brass band. Great fun! Later, I bought myself a valve trombone, which I tootled on from time to time. But my musical sensibilities have become much more sophisticated and developed over time – and I could no longer bear to hear myself play.

Do you play music when you are writing?

No, never, as much as I would like to. Writing for me is an all-engrossing activity. I am a ‘visile’ – I have to see the story unfolding before my eyes before I can write it.

If you were cast ashore on a deserted island, what five musical pieces would you choose to have with you?

Oh, a difficult question! But put on the spot, here they are –

- Vaughan Williams, ‘Sinfonia Antarctica’ : the most atmospheric sea piece I know

- Stanford, ‘Songs of the Sea’ : so rousing and heart-lifting

- Sibelius, ‘The Tempest’ : especially the mysterious Berceuse

- ‘Cats’ : I’m not really a fan of musicals but Lloyd Webber really captures the feline spirit

- Mike Oldfield’s ‘Hergest Ridge.’ : from my youth, when courting the lovely woman who would become my wife…

Besides listening to music, what do you like to do in your spare time?

Doesn’t seem to be much spare time these days. Kathy and I do enjoy walking – Devon has some wonderfully scenic areas to explore – and I’m also partial to a delicious meal with all the trimmings and a good Red. Again, we’re very lucky to live in Devon as the produce grown here is next to none. We get an organic vegetable box regularly and it is always a delight to see what Kathy will conjure up from the exotic ingredients.

Why did you recently decide to initiate a move to a brand new website?

This was prompted by the retirement of the Bosun, who’d compiled a great newsletter for over ten years. But things move on, and it was a chance to look at the way I interact with my readers in a holistic sense. I was already tweeting, and posting on Facebook and Pinterest so it seemed a good idea to start a personal blog. A website with all the information about me and my books plus an interactive blog seemed to fit the bill. Feedback so far has been very positive.

I think social media are becoming more and more important for authors today. When the first Kydd novels came out a decade or so ago no-one had heard of twitter and the like and blogs were uncommon.

Although these are all time-consuming I find I am enjoying the participation greatly – and as long as I am disciplined about the time I spend writing the Kydd books I hope to explore other possibilities, too.

What are you working on now?

I have just signed a new three-book contract for the Kydd series and am busy working on the next book, which will come out October next year. Its working title is ‘Pasha’ but I won’t give the game away just yet. I have to deliver it to my publisher by January 1 – so there’s no pressure…

Copyright notices

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

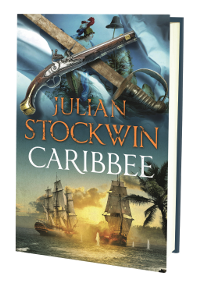

Cover Story: CARIBBEE

Posted on October 25, 2013 17 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

I know I’m privileged to be consulted at every stage of the conceiving of and production of a Kydd Series book cover; this isn’t the case for all authors. Thank you, Hodder & Stoughton!

I know I’m privileged to be consulted at every stage of the conceiving of and production of a Kydd Series book cover; this isn’t the case for all authors. Thank you, Hodder & Stoughton!

While some might argue that it’s the inside that counts, the cover is the billboard for the book. As any one title is competing with many thousands of others it’s very important to draw a potential reader to your book with an eye-catching jacket.

So, how did the splendid cover of CARIBBEE come to be?

Once my editor Oliver Johnson had read the manuscript he emailed to invite any thoughts I had – and of course spoke with his colleagues in the Marketing, Sales and Publicity Departments.

In CARIBBEE, while there’s plenty of action and engagement with the enemy, it’s somewhat lighter in tone than BETRAYAL so I suggested a cover that was a change from its darker hues. And as the location is the Caribbean, exotic sunny colours, please!

Oliver decided to go with a layout similar to the previous two books with eighteenth-century naval weapons against an appropriate flag at the top, frigates in combat at the bottom of the page and a hint of the locale in some form.

Various images were sourced – a boarding pistol, a sea service cutlass and a flag of the Batavian Republic (Curacao reference).

These were then sent, along with a design brief, to Larry Rostant, who’s an incredible digital artist. (He’s done cover art for Stephen King, George RR Martin etc.)

While I knew in a broad sense what the cover would look like by this time seeing Larry’s fabulous creation was a real buzz. Some books have a ‘shout line’ – perhaps a quote or some reference to the story but as one Hodder employee remarked – ‘The cover is gorgeous, it says it all!’ I must say I had to agree.

– Do you have a favourite Kydd Series cover? I’d love to hear your thoughts –

Copyright notices

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice