AskJules: Naval headgear

Posted on December 17, 2013 5 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

Ken Smith was curious about naval headgear in Kydd’s day:

‘I was thinking about marines in the fighting tops. What kind of hat did they wear? Did it get in the way of fighting? Was it just decorative or did it serve a purpose? How about officers: tricornes, bicornes, fore and aft, side to side. Did they have a choice or was everything “uniform”?’

‘Thanks for the question, Ken. The Georgian Navy was colourful and individualistic in its headwear.

Both sailors and officers had different ‘levels’ of attire at sea – sensible working rig, and clothing more suited to a formal occasion or going ashore. For officers this division was broadly ‘undress’ uniform and full ‘dress’ uniform. As well as being an indication of rank/rate, headwear kept the elements at bay – both sun and rain. Many chapeaux were coated with a water-proofing.

It surprises many that Jack Tar actually didn’t have an official uniform before 1857. His typical outfit in Kydd’s day was ankle-length white “trousers” and a short blue jacket. Shirts were often a colourful red check, and it was a euphemism for punishment by the lash to be said to have been given a ‘red-checked shirt at the gangway’. Many sailors wore a kerchief at the neck. This could be knotted around the head in battle to keep sweat from running into the eyes. A cocked hat would be useless up in the rigging as it would be easily blown away – a sailor often chose a hat with a small brim made of leather or straw with a ‘chin stay’ to keep it in place, or a woollen or fur “monmouth” cap.

Officers’ uniforms were prescribed by the admiralty at various times – 1795, 1812 etc. but these were really only guidelines and there was a range of sartorial flair shown, especially amongst officers with private means. Bicornes were the most fashionable headgear by 1800, really the well-known tricorne with its front retracted and therefore worn crossways. By 1805 flatter bicornes were the more popular, worn “fore and aft”, although more conservative officers wore them in the old style.

In general, the uniforms of the marines followed those of the army, with a lag of a few years. In the late eighteenth century marines wore the standard light infantry hat with a large plume over the top. By the early years of the nineteenth century when honoured with the title ‘Royal Marines’ headgear was a hat (made of glazed leather) without a feather, cocked up to one side by two tapes.

The full marine uniform was worn for guard duty aboard ship and for landing parties. No doubt in the height of action jackets were removed and hats set aside or knocked off. This would have been even more the case in the fighting tops, where a cap could be blown off.

Marine officers wore cocked hats; three-cornered in the eighteenth century, two-cornered in the nineteenth century.’

- And speaking of headwear, there’s a Navy blue Kydd Cap up for grabs – what is the name of the stunning Turkish award Nelson wore on his cocked hat? Deadline for entries: December 20. First correct entry drawn wins. Please include your postal address. Answer below or email julian@julianstockwin.com

> Do you have a question for ‘Ask BigJules’ – fire away! I’ll answer as many as I can in future posts…

Copyright notices

Boatswain: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Battle of Trafalgar: By Denis Dighton [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

Jack Tar

Posted on December 14, 2013 7 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

One of the most familiar icons of British maritime history is Jack Tar, the sailor.

We don’t know for sure where the moniker ‘Jack Tar’ come from. The word ‘tar’ as a familiar term for a sailor probably dates back to the seventeenth century. It was sometimes prefixed by ‘jolly’. Tar, of course, was pretty pervasive on board ship, used as a waterproofing agent (tarpaulin) and by a seaman to dress his queue, his clubbed plait of hair. ‘Jack’ was frequently a generic name for the common man. The term ‘Jack the Tar’ was used in an engraving of 1756 about the Seven Years War. And in 1770 an essay compares someone to ‘a Jack-tar on the quarter-deck.’

A Jack Tar was said to be:

-

Begotten in the galley and born under a gun

Every hair a rope yarn

Every tooth a marline spike

Every finger a fishhook

And his blood right good Stockholm tar

The period in which I’m particularly interested, and which is the setting for my Thomas Kydd series, is the zenith of the Age of Sail (1793-1815). It coincides with the monumental strugle for empire between Britain and Napoleonic France.

In the bitter French wars at the end of the 18th century, there were, out of the six hundred thousand or so seamen in the Navy over that time, only about 120, who by their own courage, resolution and brute tenacity made the awe inspiring journey from the fo’c’sle as common seaman to King’s officer on the quarterdeck. This meant of course that they changed from common folk to gentry; each became – a gentleman. And that was no mean thing in the 18th century. And of those 120, a total of about 22 became captains of their own ship – and a miraculous three, possibly five, flew their own flag as admiral!

It’s important to take account of the historical context in which Jar Tar lived. Conditions aboard were hard, but for the times by no means extreme. On the land there was no real security for the working man; a full belly at the end of a hard day was never certain, and food was generally of poor quality. At sea, the meanest hand could rely on three square meals a day and grog twice – and free of charge, something a ploughman in the field or redcoat on the march could only dream about.

Accommodation at sea was far cleaner than the crowded bothies and stews of the city and with half the men on watch it has been remarked that the 28 inches of hammock space per man compares favourably with that of a modern double bed. It may be a life we couldn’t tolerate today, but for the eighteenth century it was not horrific.

Jack Tar’s world, the lower deck, was a unique, colourful and deeply traditional way of life, with customs and attitudes hallowed over the centuries. A young sailor learned many things along with his sea skills: handicrafts ranging from scrimshaw to ships-in-a-bottle, well-honed yarns whose ancestry is lost in mists of superstition, and most valuable, the social aptitudes to get on with his fellow man under sustained hard conditions.

Individualism – a trait shared by all nations in a universal sea ethos – made for strong characters and sturdy views and makes a nonsense of portrayals that have them otherwise. There could be no doubts about the man next to you on the yard or standing by your side to repel boarders; they were your shipmates, and a tight and supportive sense of community arose which only deepened on a long commission, far waters and shared danger. Then, as now, the sea was a place to find resources of courage and endurance from within yourself, to discover the limits, both in you and in others.

Prize money was an obvious incentive to Jack Tar – all seamen would have before them the example of the capture of the Spanish Hermione, which left the humblest seaman with forty years’ pay for just a few hours work. Such riches were rare, but by no means unknown – yet this does not explain why the blockading squadrons, storm-tossed and lonely with never a chance of a prize, still performed their sea duties to a level that has rarely been seen, leagues out to sea and out of sight, executing complex manoeuvres without ever an admiring audience.

A more universal reason is perhaps the fact that there was a simple and sturdy patriotism at work; in the years since Drake, the seamen had evolved a contempt for those foreigners who dared a challenge at sea, and in the years of success that followed, it became a given that the Royal Navy would prevail, whatever the odds. In the century up to Nelson this became a ‘habit of victory’ that gave an unshakeable confidence in battle, every man aware that he was a member of an elite with a splendid past that it would be unthinkable to betray. This habit of victory produced some incredible results. For example, in the whole 22 years of the war, the Royal Navy lost 166 ships to the enemy. In the same period no less than 1,204 of the enemy hauled down their colours in return – seven times their number!

‘Aft the more honour, forward the better man!’

The men on the lower deck who helped achieve these odds were exceptional seamen, tough and loyal characters who have contributed to a sea culture that has flowered and endured over the centuries. They’ve often been painted as mere brutes but that is certainly not the case. It’s time for the real Jack Tars to step out from the shadows and take their place among the heroes of the age. Nelson was adamant, and I have his words as the dedication to my first book, speaking of the officers aft on the quarterdeck and the men forward in the fo’c’sle; ‘Aft the more honour, forward the better man!’

As an aside, one of my most abiding images of Jack Tar is something that happened just before Nelson was finally laid to rest in St Paul’s Cathedral. The solemn funeral service lasted over four hours. Beneath the dome of St Paul’s hung a chandelier of 130 lamps, and below the floor of the aisle a special lift had been built to lower the coffin into the crypt. Then, at the last moment, when the 48 seamen from Victory were to fold the battle ensign and lay it upon the coffin they turned on the flag and tore it into pieces, as a remembrance for each man. An impulsive, emotional initiative worthy of Nelson himself.

A similar article was also posted at English History Authors Blogspot

Copyright notices

Poster: [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; Pascoe: [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; Nelson’s funeral: (Image: By Augustus Charles Pugin.Neddyseagoon at en.wikipedia. Later version(s) were uploaded by Gump Stump at en.wikipedia. [Public domain or Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons)

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

The Cuban Grandmother

Posted on December 10, 2013 1 Comment

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

I’m delighted to launch a new BigJules feature – Reader of the Month!

The first Reader of the Month is Martha Berry. A few years back Martha got in touch with me saying how much she enjoyed my Kydd tales, signing off as ‘the Cuban Grandmother’. Martha is now also a great-grandmother… She has three daughters, five grandchildren and three great grandchildren!

Martha was born an raised in Cuba and studied physics and chemistry there. On marrying Dr Charles Berry, the couple moved to the States. Sadly, after Castro took over the island she was never able to return. Martha undertook cancer research for USC Medical School for a time then obtained teaching credentials and taught math and science. She later moved into counselling and guidance.

The word retirement doesn’t seem to be in Martha’s vocabulary! As well as being matriarch of a large extended family she still works in the field of special education, teaches and counsels.

Martha says she has always been a romantic, perhaps born in the wrong era. She loves historical fiction but at school in Cuba detested factual history. ‘No one who had to read and memorize from the 4th to 12th grade all the Christopher Columbus trips to the New World could have developed a love of ships and the sea!’

Martha has read all Patrick O’Brian’s books twice and is doing the same with the Kydd books.

Does she have a favourite Kydd title?

‘How can anyone choose one? If you insist I pick one I will say the first book because it gave us the whole background of this poor young man who gets taken away by force from all he knows and loves. There was not a thing he could do to change his situation. We could predict though, by reading carefully this young man’s character, that he would eventually achieve what he deserved.’

She adds: ‘I love Renzi. A very complex man! He adds much to the books.’

And Martha had these comments on CARIBBEE: ‘I read this book in two nights. I could not put it down. Needless to say, you have not lost your touch. It was wonderful. I am very familiar with hurricanes. In Cuba they don’t name them, just refer to them by year. The waterfront would become an unbelievable sight. The waves would come over the retaining wall and move inland for blocks. The doors were nailed shut as if one door blew open and the others remained closed, the roof could be blown out. One year we prepared the house and the broadcasting company announced about midnight that the danger was passed. My father took out the nails and we went to bed. At 3:00 am the ‘ciclon’ decided to strike. It was a night to remember!’

And she concludes: ‘I can hardly wait for the next book. I get the impression that we will read a new chapter about Renzi and Kydd’s sister. Yeah! I hope so. ’

——

Would you like to be a candidate for Reader of the Month? Just get in touch with a few sentences about your background and why you like the Kydd series. Each published Reader of the Month will receive a special thank-you gift

Seafaring Cats

Posted on December 4, 2013 4 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

When it became apparent that the mighty 140-gun first rate Spanish ship-of-the-line Santisima Trinidad would not survive the raging storm that followed the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805 every effort was made to save those souls still alive on board. Officers and seamen were lowered with ropes from the stern and quarter galley windows as boats from nearby British warships came to rescue them. A lieutenant from HMS Ajax, whose boat was the last to leave the scene, reported, “Everything alive was taken out, down to the ship’s cat.” The boat had put off from the starboard quarter of Santisima Trinidad when a cat ran out on the muzzle of one of the lower-deck guns and gave a plaintive miaow. Ajax’s boat promptly returned to the stricken ship and carried the grateful creature off to safety.

Scratch most mariners and you will find a soft spot for cats. I remember during my own time at sea hulking great engine room stokers lovingly crafting miniature hammocks for the ship’s cat from scraps of canvas.

My own two Siamese cats Chi and Ling here act as on call literary muses as I write my novels about the Age of Sail. Despite their undoubted contribution to my daily wordage, sadly they seem to have no sea-going ambitions!

Since very early times cats were thought to bring good luck aboard ship, a belief that interestingly crossed cultures. Japanese sailors, for example, favoured tortoiseshell cats, to protect them from ghosts and give warnings of storms.

And of course when grains and foodstuffs aboard were stored in bulk, cats were indispensable in keeping rats and mice at bay.

But I’m sure it was for their companionship and affection that cats have been most valued by seamen over the centuries. (Pets are no longer allowed in the Royal Navy and many other navies. Fear of rabies led to a ban in the 1970s.)

Of all the sea-going cats who have enriched people’s lives over the years I’ve picked my favourite three – Trim, Simon and Oscar.

Trim

Trim was a ship’s cat, much beloved of the navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders. Born in 1799, aboard a ship ’roundabout’ on a voyage from the Cape of Good Hope to Botany Bay, the kitten fell overboard, but managed to swim back to the vessel and climb aboard by scaling a rope. Taking note of his strong survival instinct and intelligence, Flinders and the crew made him their favourite.

Trim sailed with Flinders on HMS Investigator on his 1801-03 voyages of circumnavigation around the Australian mainland, and survived the destruction of Porpoise on Wreck Reef in 1803. When I wrote COMMAND I took special delight in having my fictional hero Thomas Kydd meet Flinders – and Trim – in the penal colony of New South Wales.

When Flinders was accused of spying and imprisoned by the French in Mauritius on his return voyage to England Trim shared his captivity until he unexplainedly disappeared. Flinders believed he had been killed and eaten.

Trim was black, with white paws, chin and chest. He was named after the butler in Laurence Sterne’s ‘Tristram Shandy’, because Flinders considered him to be a faithful and affectionate friend. During his incarceration Flinders wrote a biographical tribute to Trim, part of which is quoted on a plaque under a bronze statue of Trim at the Mitchell Library in Sydney, Australia.

TO THE MEMORY OF TRIM

The best and most illustrious of his race

The most affectionate of friends,

faithful of servants,

and best of creatures …

Simon

Simon was born in 1947 in the naval dockyard in Hong Kong. He was smuggled aboard the sloop HMS Amethyst by Ordinary Seaman George Hickinbottom.

Aboard ship he was much loved by the crew, including the captain, who only had to whistle and Simon appeared at his side. Simon loved to curl up inside his upturned gold-braided cap when it was not being worn.

Amethyst was ordered to sail up the Yangtze River to relieve the guardship HMS Consort who was protecting the British Embassy at Nanking during the Chinese Civil War between the Kuomintang and the Communists. During the voyage Amethyst came under heavy fire from shore batteries on April 20, 1949 and a series of direct hits crippled the ship. Fifteen men were killed, including the captain and many were wounded. Simon was among the casualties with several wounds from shrapnel.

The ship ran aground and some of the crew managed to swim to safety but 50 remained on board. HMS Consort came to their aid but also came under heavy fire with casualties. Other rescue attempts resulted in more losses. For more than three months Amethyst was held captive by the communists and denied any supplies, insisting that the captain sign a statement that the ship had wrongly invaded Chinese national waters and had fired on them first.

Simon saved many lives by protecting the dwindling food stores from the infestation of rats even though he was still recovering from his wounds. One particularly bold and vicious rat was named ‘Mao Tse Tung’ by the sailors. Simon dealt with him in short order.

He also boosted morale in the sick bay by sitting on the bunks of the wounded and allowing himself to be fussed over. His courage was a tonic for the embattled crew who kept a running list of his kills. For war-weary Britons he became a plucky symbol of resistance.

Amethyst finally made a run for open waters on July 31 under cover of darkness and broke through the boom at the head of the river at full speed.

By the time the ship had returned to the UK on November 1, 1949 Simon had become a celebrity and thousands of letters were written to him. Lt Cdr Stuart Hett was appointed Amethyst’s Chief Cat Officer to deal with his fan mail. Simon was put in quarantine but there he pined for his shipmates and died. He received, posthumously, the prestigious PDSA Dickin Medal, the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross.

Oscar

Oscar was the ship’s cat aboard the German battleship Bismarck. When the ship was sunk in 1941, only 116 out of a crew of more than 2,200 survived. Oscar was found shivering on a plank amidst the wreckage of Bismarck and was picked up by the crew of the destroyer HMS Cossack, which was in turn hit and sunk, a few months later, killing 159 of her crew. Again, Oscar survived.

The plucky feline then became the ship’s cat of HMS Ark Royal but shortly after his arrival, the ship was torpedoed and a bedraggled Oscar once again was pulled from the sea, ending up back in Gibraltar.

By now he was seen as a Jonah and not surprisingly, offers to return to sea were not hugely forthcoming, but there on land he took up residence in the office of the Captain of the Port. He saw out the end of his days in style in the dockyard, though, as somewhat of a celebrity. He was given a new job as mouser-in-residence at the governor general of Gibraltar’s office. He eventually returned to the U.K. and lived out his years at the Home for Sailors.

A version of this article first appeared in “Quarterdeck”

An Excerpt from KYDD……Worn out by the trials and challenges of the day, some instinct drove him ever down to seek surcease in the deepest part of the ship. He found himself in the lowest deck of all, stumbling along a narrow dark passage past the foul smelling anchor cable, laid out in massive elongated coils.Kydd felt desperately tired. A lump rose in his throat and raw emotion stung his eyes; utter despair clamped in. He staggered around a corner and just at that moment the lights of a cabin spilled out as a door opened. It was the boatswain, who looked at him in surprise. “Got yourself lost then?” he said. “Nowhere t’ sleep,” mumbled Kydd, fighting waves of exhaustion. “Jus’ came on the ship today,” he said. He swayed, but did not care.

He considered for a moment. “Come with me.” He pulled at some keys on a lanyard and used them to open a door in the centre of the ship. “We keeps sails in here. Get your swede down there ’til morning, but don’t tell anyone!” He turned on his heel and thumped away up the ladder. Kydd felt his way into the room. It stank richly of linseed oil, tar and sea-smelling canvas, but blessedly he could feel the big bolsters of sails that could serve as his bed, and he crumpled into their soft resistance. He lay on his back, staring up into the darkness at the one or two lanthorns in the distance outside that still glowed a fitful yellow. Cutting into his surging thoughts, his feral instincts jerked him into full alert. He knew for a certainty that he was not alone. His mind flooded with primitive fears; he sat up, straining to hear. Without warning, a shape launched itself straight at him. He mouthed a scream; but with a low ‘miaow’ there was a large cat on his lap, circling contentedly. Kydd stroked the creature compulsively, again and again, the contrast between its warm furry trust and his recent experiences overwhelming. The cat purred in ecstasy before stretching out comfortably and settling down. Kydd crushed the animal to him, and first one tear, then another fell on its fur… |

Copyright notices

Trim: Rodney Burton [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Cat in hammock: By Beadell, S J (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Bismarck: Bundesarchiv, Bild 193-04-1-26 / CC-BY-SA [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

Punch, anyone?

Posted on December 1, 2013 6 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

With the Festive Season upon us, it’s easy to partake of perhaps a little too much of the grain and grape.

The Georgians could certainly drink their fill. Judging by household accounts for hogsheads of ‘sack’, ‘port’ and ‘canary’ they very seldom drank water, which was often unsafe. Beer or ale was very popular with all classes. (‘Sack’ and ‘canary’ were fortified white wines from Spain or the Canaries.)

But it was punch that was often the cause of the worst thumping heads the next day, especially for members of gentlemen’s clubs.

The popular ‘Regent’s Punch’ was named after the Prince of Wales. The recipe called for three bottles of Champagne, two of Madeira, one of Hock, one of Curacao, a quart of Brandy, one pint of Rum and two bottles of water – along with four pounds of raisins, sliced Seville oranges, lemons, white sugar and iced green tea.

But even the Georgians would be hard pressed to beat the feat of the Right Honourable Edward Russel, commander-in-chief of His Majesty’s forces in the Mediterranean. He served a rather special punch from a marble fountain in his garden at Alicante, Spain. The ingredients included four hogsheads of Brandy, eight hogsheads of water, 25,000 lemons, 165 pints of lime juice, 1450 lb of sugar, 5 lb grated nutmeg, 300 toasted biscuits and a pipe of dry mountain Malaga.

Russel had a special canopy built to keep off the rain (you wouldn’t want it diluted, would you) and a ship’s boy actually rowed around the fountain in a mahogany boat, filling the cups of the 6000 guests. When the poor lad became overcome with fumes, another took his place.

Bottoms up! And all the best for the Festive Season.

(A hogshead is a large wooden cask = roughly 52 gallons, a pipe = double that)

Copyright notices

Hogarth print: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

Navies: three books, three centuries

Posted on November 27, 2013 Leave a Comment

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

An enticing selection of review copies of books arrived in my postbag recently, all from Seaforth. Each very different but together spanning three centuries, celebrating people and ships of the world’s navies, predominantly the Royal Navy.

“British Battleships. 1889-1904”

by R A Burt, Seaforth

Indispensable for students of the pre-dreadnought era, this is a revised reissue of the third of R A Burt’s magnificent trilogy on British battleships. As the author says in his preface, after the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, Great Britain enjoyed a naval supremacy that was virtually unchallenged until the latter part of the 19th century. The Russian war scare of 1884 and the public’s anxiety about the Royal Navy’s ability to fight a modern war at sea, prepared the way for the Naval Defence Act of 1889 and a vast programme of warship construction. Over the next twenty years a fleet of fifty-two battleships was built. The book includes many new photographs and extensive tables and schematics as well as full technical history and careers of the ships.

“A Biographical Dictionary of the Twentieth Century Royal Navy,Volume 1”

by Alastair Wilson, Seaforth

This covers admirals of the fleet and others. It is the first volume of a major study intended to provide a resume of the service lives of every flag officer in the style of the great nineteenth century biographical dictionaries of Marshall and O’Byrne.

Accompanying the book is a CD (over 600,000 words) that contains the services histories and careers of 336 most senior admirals on the Navy List from 1900 onwards. A wonderful tool for historians and anyone interested in naval genealogy. (The records on the CD are fully searchable.)

“World Naval Review. 2014”

Edited by Conrad Waters, Seaforth

Launched in 2009, this annual is an authoritative summary of happenings in the naval world during the previous twelve months. Nine expert contributors provide both national and global perspectives. Highlights of this issue include a survey of torpedo developments, analyses of significant new warship classes and German AIP technology. Extensive illustrations and photographs accompany the text.

Series v Standalone

Posted on November 24, 2013 33 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

Debut book of the Series

Latest title in the Series

It’s a question I’ve been asked quite a few times: Do I need to start at the beginning of the Kydd series if I want to read your books?

Well, this is a personal choice. Each of my books is a standalone, with enough back-story to fill in any gaps if you haven’t read earlier titles.

The series does have a theme – one man’s journey from pressed man to admiral in the age of fighting sail – but each book is a segment of Kydd’s life, a story in itself.

I know some people like to read a series chronologically but I can also see that a newbie Stockwin reader might finish, say, CARIBBEE (my latest book), and then want to read SEAFLOWER, when Kydd was first in those turquoise seas – and a much different person.

And if a commitment to read fourteen titles might seem a bit much to busy people, I always suggest taking in a random one, picking a cover or location that most appeals and taking it from there…

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. How did you discover the Kydd books? Did you read one and then go back to the first? Or have you read a few in no particular order? Have you re-read the series several times?

I’ve put together this summary of the series to date, with the books in chronological order. You can also download or share this as a PDF.

The Sea Painters: Turner

Posted on November 22, 2013 2 Comments

Joseph Mallord William Turner, the greatest of the English Romantics and colourists, (1775-1851) was born in London, a stone’s throw from the River Thames. His father (like Tom Kydd’s) was a wig-maker.

Although he painted many subjects, water would hold a fascination for Turner for the whole of his life. His seascapes range from peaceful early morning vistas of fisherfolk on the sands to incredibly violent storm scenes to experimental, impressionist creations. I particularly like his storms!

The story that Turner had himself lashed to the mast of a ship so that he could experience a storm at sea has never been verified – but I like to think it may well be true…

It has been estimated that two thirds of Turner’s paintings are to do with the sea in some form. National Maritime Museum Curator Christine Riding says: ‘It was his great subject, because I think it suited his temperament perfectly – ever changing, ever dramatic, different in every light and weather, violent or calm, and often used to represent the state of the island nation.’

Turner’s work is valued not just for its intrinsic appeal but also as potent social or moral commentary. This is true of his iconic ‘The Battle of Trafalgar’, commissioned by King George IV in 1822. The painting combines a number of incidents from different times during the battle and some have criticised this as a departure from the historical record. But I feel that artists are entitled to reflect their feelings in their work and the message is clear – a glorious victory, yes, but the suffering was great and the cost to the nation was more than the death of a national hero.

Another of his most famous works, ‘The Fighting Temeraire’ (voted the nation’s favourite painting) again takes liberties with reality. It is a stunning work however. You can read so much into it, not just the passing of the age of sail to steam, but death and regeneration…

I was delighted to receive a review copy of a book published to coincide with a major exhibition at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. Entitled ‘Turner & the Sea’ it’s a magnificent nearly 300-page visual celebration of the great artist’s range and skill in his engagement with the sea. The majority of the 200 paintings in oil, watercolours, etching and sketches are by Turner but the book also contains works by a number of other artists who were influenced by Turner. As well, eight contributors to the book bring new scholarship to our appreciation of how Turner responded to the maritime art of the past while challenging his audience with new ways of representing the sea. A treasured addition to my library!

I plan future blogs on some of the other maritime painters I particularly admire.

The exhibition of Turner’s sea paintings runs from today until 21 April 2014.

Copyright notices

All images: J. M. W. Turner [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

Cauls, Mary Carleton and the Chatham Chest!

Posted on November 20, 2013 4 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

In our household I’m the hoarder; not only physical artefacts from the past, numerous tins of assorted screws & wires, books & journals – but countless snippets and esoteric facts from the Golden Age of Sail. Over the years I’ve filed these away, adding to them when I started the Thomas Kydd series and began extensive research on the Georgian Navy. Someone once said that an author only uses 10% of the research he undertakes, but you never know which 10% that will be! So true! And this was the reason I wrote STOCKWIN’S MARITIME MISCELLANY. It gave me a way to share some of the fascinating facts and sea lore I’d tucked away.

So – cauls, Mary Carleton and the Chatham Chest! Just three of the hundreds of items in my little non-fiction title.

The Caul

The thin membrane covering the heads of some new-born children was esteemed by Old Salts. They believed it would guard against drowning and shipwreck. One advertisement in a Georgian newspaper announced the sale of a caul ‘having been afloat with its late owner forty years, through the periods of a seaman’s life and he died at last in his bed, at his place of birth.’ Sailors paid handsomely for these talismans, often sewing them into their canvas trousers. (Back in ancient Rome lawyers also favoured the caul, taking it to guarantee they would be eloquent and successful in all their cases, but I digress…)

Mary Carleton

Port Royal, until it was swallowed by the sea, was ‘the richest and wickedest city in the world’. Some of its ladies of the night have gone down in history with names like No-Conscience Nan and Salt-Beef Peg but the most famous of all was one Mary Carleton. A contemporary wrote of her: ‘A stout frigate she was or else she never would have endured so many batteries and assaults… she was a common as a barber’s chair; no sooner was one out, but another was in.’

The Chatham Chest

The world’s first occupational pension. From 1590 all seamen in the Royal Navy made a contribution of six pence per month to support the Chatham Chest, which paid pensions to injured seamen. The assets of the fund were kept in an actual chest at Chatham dockyard, secured by five locks, which opened to five separate keys held by five different officers – an expedient intended to prevent misappropriation of the funds. The chest exists to this day and may be seen at the Chatham Historic Dockyard museum.

Copyright notices

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

Sim’s Treasures

Posted on November 17, 2013 5 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

Over the decade or so that I’ve been a writer I’ve been privileged to meet many collectors, modellers, academics and historians who share my love of the Age of Fighting Sail. They’ve all been generous in giving of their time, and in some instances, allowing me special access to precious artefacts and documents

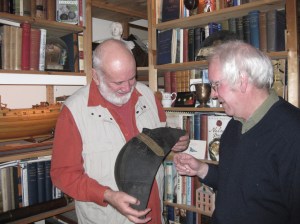

Admiring a bicorne in Sim’s collection It belonged to a lieutenant during the period 1812-1825 Sadly, his name is lost to history

One such collector is Sim Comfort whose wonderfully eclectic treasure trove of coins, medals, paintings, swords and other naval items has been built up over a many decades. I must admit I found it very hard to disengage from the delights in Sim’s study when I visited!

From Webster Groves, Missouri, Sim joined the US Navy at age 18. The US Naval Security Group sent him to Guam and later to London, where the National Maritime Museum sparked a life-long love affair with British naval history.

Sim with some of his treasures, including Broke’s fighting sword, at a ceremony earlier this year to mark the 200th anniversary of the HMS Shannon and USS Chesapeake engagement

Sim has published a number of fine reprints on naval subjects, including David Steel’s ‘Elements and Practice of Rigging and Seamanship.’ He has also authored two books based on his collection, ‘Forget Me Not’ (a study of naval and maritime engraved coins and plate) and ‘Naval Swords and Dirks’ (British, French and American weapons, 1730-1830).

A new volume on Nelson’s swords will be published next year.

Recently Sim played a major role in setting up a Loan Exhibition of Miniature Naval Portraits, at which many pieces from his collection were shown. With Sim’s kind permission I’m delighted to be able to share the 68-page catalogue. It’s fascinating reading! Contact me on julian@julianstockwin.com and I’ll email you one

The boatswain looked at him narrowly. “That’s right—saw you at the fore capstan. Well, lad, don’t worry—First Luff has a lot on his plate right now, sure he’ll see you in the morning.”

The boatswain looked at him narrowly. “That’s right—saw you at the fore capstan. Well, lad, don’t worry—First Luff has a lot on his plate right now, sure he’ll see you in the morning.”