The Birth of a Book: CARIBBEE

Posted on October 24, 2013 11 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

CARIBBEE is the latest title in my Thomas Kydd series and as it’s officially launched into the world today it’s a pretty special time (as is true for most authors, I guess) – seeing your creation, the work of at least a year – now out there for all to read, to (hopefully) enjoy, to review, to comment on…

As I’m writing a series I plan a number of my books ahead so that I know in broad terms what will be covered in succeeding titles. This was certainly the case with CARIBBEE as I’d decided that after the ill-fated expedition in South America in BETRAYAL, L’Aurore would be sent to Barbados to plead for reinforcements and thereby enter an entirely more agreeable scene.

The genesis of CARIBBEE actually goes back to 2002, when Kathy and I headed off on location research for SEAFLOWER.

But the big difference of course between these two books is that in CARIBBEE Kydd is a post captain, something he could never have dreamed of on his first visit to these shores as a young seaman.

My working year now revolves around various set events. As soon as I’d delivered the manuscript for BETRAYAL to my editor at Hodder & Stoughton, Oliver Johnson, on January 1, 2012, I moved all the research material, planning notes etc. for that book into an archive file and opened new files in my computer for CARIBBEE. Quite a deal of my earlier work for SEAFLOWER was relevant but there was much new material to research and digest.

The Kydd Series follows the actual historical record so the first stage of my research was a detailed examination of what was going on in Kydd’s world in 1806/7, especially in the Caribbean. The West Indies was hugely important to Britain. At the start of the Napoleonic wars four fifths of all overseas Exchequer receipts came from these parts. There were also some interesting geo-political aspects, Napoleon’s Continental System among them. And slavery was still being practised. Lots of meat and drink for a writer!

But the research is only the first step. Foremost is the imperative to tell a story, a good dit. This means having a strong narrative thread, and several related ones; consolidating the stakes of the book; deciding on viewpoints – all the questions that have to be answered in order to craft a novel.

So once I’d finished my preliminary research – a couple of months – it was time to dust down the White Board and Kathy (who works very closely with me on many aspects) and I sketched out the broad outlines of the story. Among other things this generally throws up areas that need more research.

I find the planning and detailed research stage takes about six months; writing, the other half of the year.

During the course of writing a book there are always things that pop up – plot problems, character niggles, narrative balance. Kathy and I walk and talk these along the bank of the River Erme. Our rule: we can’t return until resolution is arrived at! I think the record is six hours for one particularly knotty problem.

After careful editing and checking, CARIBBEE was delivered on January 1 this year. It’s always a bit of a nail-biting time but Editor Oliver Johnson came back pretty swiftly:

‘A beautifully engrossing, often sweet and pulse pounding novel. A very fine addition to the Kydd oeuvre… I couldn’t put it down. I loved the excursion to the west coast of Jamaica and the Tysoe backstory. The hurricane section contained some of the most thrilling sailing scenes I can remember. Hurricane apart, your book made me want to ditch my keyboard and head to warmer climes. Oh, for a draft of Blue Mountain coffee… You are non pareil in the field!’

Champers cracked that night!

I’ve been very fortunate to have had Hazel Orme as my copy editor since book one; she’s probably the best in the business! Hazel spots any inconsistency or grammatical error and prepares the manuscript for typesetting before it’s sent off to the printer.

As this is happening, Hodder’s Sales & Marketing team are thinking about how they are going to present the book to the trade. About this time cover discussions are started – but that’s the subject of my blog post tomorrow…

The Immortal Memory

Posted on October 21, 2013 13 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

Today is the anniversary of Horatio Nelson’s great victory – and mortal wounding – at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

At the time a sailor in Royal Sovereign wrote to his father back in England, ‘Our dear Admiral Nelson is killed. All the men in our ship… have done nothing but blast their eyes… chaps that fought like the devil sit down and cry like a wench.’

Admiral Collingwood confided in his official despatch, ‘My heart is rent with the most poignant grief.’

And Scott, Nelson’s confidential secretary, who had comforted Nelson as he died, said: ‘When I think, setting aside his heroism, what an affectionate, fascinating little fellow he was…I become stupid with grief for what I have lost.’

Nelson’s Mortal Wounding

One of the four bronze panels on the pedestal of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square

So many aspects of Nelson’s all-too-short career should be celebrated. Here are just six that have special resonance to me.

- In an age when there was an enormous divide between the fo’c’sle and the quarterdeck he openly championed the courage and skill of Jack Tar. Speaking of the officers aft on the quarterdeck and the seamen on the fo’c’sle he said: ‘Aft the more honour – forward the better man!’ It is the dedication I have in my first book

- Nelson believed in leading from the front and often performed acts of extreme bravery. In 1797, for example, when he saw a Spanish gunboat flotilla off Cadiz, the British fleet meanwhile at anchor, he called away his own admiral’s barge and with Captain Fremantle and eleven seamen was soon pulling vigorously toward the Spaniards. Inspired by the sudden intervention of their leader the British seamen raised the cry of: ‘Let’s follow the Admiral, lads!’ and made after him. A fierce, close‑in, cutlass‑clashing boat action was soon to follow. Nelson didn’t have to prove anything by getting involved like this, but there he was, right out in front.

- Nelson appreciated the importance of detailed planning but he also knew how to delegate. By inducing in his captains his own concepts of command and freely imparting his ideas and intentions to them, Nelson unlocked their initiative and reduced dependence on chancy signals. He deliberately used the concept of a band of brothers to create a tightly knit command structure, all of whom knew what he wanted without being told.

- Nelson was a man for whom courage, honour and duty shaped his life. His courage in battle is legendary. But there was also great personal courage in dealing with the many injuries and illnesses he suffered throughout his life. What person today could perform at such a high professional level with only one arm, a sightless eye, the after‑effects of malaria and other diseases, and often continual pain? And what, but an incredible belief in duty would have taken him from Emma’s arms before Trafalgar just as he’d achieved the peace he craved?

- Nelson had real humanity. The wife of Admiral Hughes described once seeing Nelson with his officers and midshipmen:

‘Among the number of thirty there must have been timid spirits as well as bold: the timid he never rebuked but always wished to show them he desired nothing that he would not instantly do himself and I have known him say, “Well, sir, I am going to race to the mast‑head and beg I may meet you there.” No denial could be given to such a request and the poor little fellow instantly began to climb the shrouds. Captain Nelson never took the least notice in what manner it was done: but when they met at the top, spoke in the most cheerful of terms to the midshipman and observed how any person was to be pitied, who could fancy there was any danger, or even disagreeable in the attempt. After this excellent example, I have seen the same youth, who before was so timid, lead another in the like manner and repeat his commander’s words.’ - Nelson had a genuine concern for the well-being all those under his command. When you read the General Order books of Nelson’s captains what stands out and what are the majority entries is not the minutiae of running the ships, or instructions for battle, but regard for the welfare and contentment of the ship’s company. There are so many, but this one seems to exemplify the rest: ‘The ship’s company are never to be interrupted at their meals, but on the most pressing occasions.’

Let us raise our glasses:

‘To The Immortal Memory.’

Copyright notices

Nelson portrait: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Emma Hamilton portrait: George Romney [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; Nelson’s column: By Eluveitie (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

BookPick: Nelson, Navy & Nation

Posted on October 19, 2013 3 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

This book celebrates the Royal Navy and the British People 1688-1815. As you can imagine, a subject dear to my heart!

With an introduction by N A M Rodger, it looks at the following wide-ranging topics – invasion and threat; patriotism, trade and empire; dockyards and industry; life afloat; expansion and victory; naval personnel in popular culture; mutiny and insecurity; Nelson and naval warfare; the experiences and weapons of war; Nelson, navy and national identity; and beyond Trafalgar – each of the eleven chapters written by a specialist in their field.

For those who would like to delve a little deeper, a useful section on further reading is provided at the end of the book, keyed to each chapter.

While the text provides fascinating insights into the Navy and British people in ‘the long 18th century’, what I found particularly engaging are the superb photographs and illustrations, some previously unseen and photographed especially for this publication. They make the price of the book worth it for them alone!

This splendid book is published to accompany a long-term gallery in the National Maritime Museum – ‘Nelson, Navy and Nation,’ opening, appropriately, on October 21. Certainly on my ‘to visit’ list…

And thanks to the publisher Conway I have a copy to give away. Just answer this question: How old was Horatio Nelson when he became a post captain? You can submit your entry via the comment box at the end of this post. Please include your full postal address. Deadline for entry: October 31.

Prick, Perique or Plug?

Posted on October 17, 2013 7 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

I first met Ken Yalden a few years ago. Ken is a keen member of the International Guild of Knot Tyers. As we chatted he recalled I had mentioned a prick of tobacco in KYDD. Recently Ken sent me a fascinating little monograph from the Museum of Knots & Sailors’ Ropework that he’s written on the method used by sailors for making a ‘navy plug’ of tobacco. Although modern sailors no longer practice this, it was well known in Kydd’s day – and with Ken’s permission I’ve extracted material from the monograph for this blog.

As with many things at sea, ‘navy plug’ has more than one name. The common name amongst sailors was ‘prick of tobacco,’ echoed by the French with the use of the word carrotte. Other names were cut plug, and plug tobacco. The word plug might stem from its shape, which resembles a tapered wooden plug used in a barrel or a bung in the bottom of a boat.

The name ‘perique’ comes from the strong flavoured dark tobacco grown in Louisiana; attributed to the Frenchman who first planted it.

Aboard ship smoking was only permitted at set times, usually outside the formal working day.

The monthly issue of tobacco to sailors was in dried leaf form, supplied in ‘hands,’ shipped in dry casks. A hand consisted of a bunch of loose leaves gathered by the stems and weighed on issue.

The hand of tobacco was spread out on a flat surface and the stalks and large veins removed. The stalks were handed back to the Victualling Office for return to the tobacco purveyor, to be ground into snuff.

The leaves were then placed onto a rectangle of cloth, commonly cotton duck. As the leaves were laid out they were sprinkled with a mixture of water and rum, then laid to overlap so that the pile in the centre was higher than those at the two sides, giving a tapered shape. The cloth was then rolled tightly by hand to make a tube, then marline hitched, much the same way as a hammock, giving it the appearance of a cigar.

Compression was brought to bear by applying a serving to the outside of the prepared tube. This was definitely a two-man job.

The perique was left to cure for some time and when unbound revealed strong smelling black tobacco, which was cut into plugs for chewing or smoking in a pipe. If the binding had been spun yarn, the Stockholm tar used in the preparation of the rope added a special dimension to the taste and colour of the tobacco…

Tobacco was officially supplied for use of ships’ companies in the Royal Navy from January 1799. Previously, it was sold by the purser, on a private basis, and the cost deducted from seamen’s wages. Although Kydd’s father had smoked a long church-warden pipe he himself had never taken up the habit. Renzi, however, did enjoy a pipe, especially on the foc’sle during dog-watches – and in KYDD, chapter 10, Tom Kydd presents Renzi with a gift of fragrant whorls of tobacco from a perique he had made; he’d learned the process from one of the gunner’s mates with whom he’d shared a watch.

Ask BigJules: Officers’ Food

Posted on October 14, 2013 6 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

Dan Abernathy asks: ‘What did the officers eat in Kydd’s day? How was it different from the men?’

‘Thanks for the question, Dan. Wardroom officers were entitled to the ordinary ships’ provisions provided for the seamen – unless they decided to subsidise their meals from their own pocket, which they almost invariably did. This was done by appointing a mess treasurer, who was responsible for ordering in extra stocks of food and wine, tea, sugar etc. It could be quite expensive – in Kydd’s day around £60 each per annum. Sometimes members of the mess who did not have private means (or prize money) were hard pressed to come up with their subscription!

Officers dined in some style. They were drummed to dinner to the tune of ‘Hearts of Oak’. As was the case ashore, dinner was in the ‘French service’ – a number of dishes (sweet and savoury) were placed on the table for each ‘course’.

The officers had their own cook; he was often quite skilled. With the advent of the Brodie Stove, the officers’ cook could produce pretty much what could be found at any fine table ashore.

Meals were served on a linen tablecloth with silver, candles and good china. Each officer had his own personal servant whose duty was to stand behind him and wait on him.

The captain dined alone, unless invited to be a guest of the wardroom mess.

The Georgian cookery writer Hannah Glasse devotes a whole chapter of her book, ‘The Art of Cookery’ to pickles, sauces, pies and other dishes ‘suitable for captains of ships’. The first entry is a recipe for ‘catchup’ that will keep 20 years!

One thing that intrigues me is the issue of a keg of ox tongues to captains on first commissioning a ship. Apparently the tradition continued well into the twentieth century! Ox tongue recipes, anyone?’

Do you have a question for AskJules? You can email me or send it via the Comments Box below. I’ll answer as many as I can in future blogs.

USS Constitution and the War of 1812

Posted on October 10, 2013 9 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

This month in 1797 a ship was launched in Boston that would come to count among the most famous ships in history, USS Constitution.

The world’s oldest commissioned naval vessel afloat, she remains in active service to this day, the United States’ designated Ship of State, visited by millions.

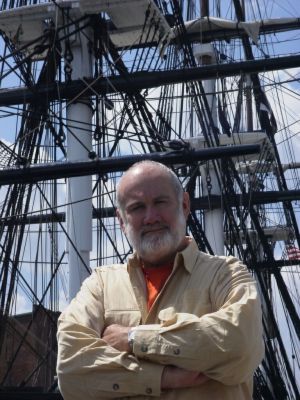

I’m particularly delighted to introduce my first guest blogger, Tyrone Martin.

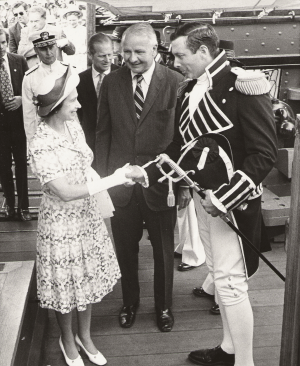

After a distinguished sea career including command of two destroyers, Commander Martin became Constitution’s 49th captain in August 1974. He hosted a visit by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth to the ship in July 1976 and is the first skipper since 1815 to have been decorated for his command tour. Since retirement, he has researched and written extensively about Old Ironsides.

For two centuries there’s been passionate outpourings from both sides of the conflict in which Constitution found herself a key player so it’s fascinating to get a perspective from a modern-day captain of the ship. Thus, without further ado, it’s over to Commander Ty Martin – and Old Ironsides and the War of 1812…

The Royal Navy had been building frigates for about a half century by the time the U. S. Navy was created in the late 1790s. In those years, the type had grown gradually in size until the latest standard RN unit was a 38-gunner armed primarily with 18-pounder long guns. Its development was the product of strategic needs to defend the empire balanced by the cost and the availability of materials.

The forty-four gun frigate didn’t originate with the nascent U. S. Navy, but in the 1790s it was a rare bird. The American version, the product of an innovative design by Quaker Joshua Humphreys, stemmed from the decision that, since the new, all-frigate USN would be minuscule, its units ought to be built stronger and more heavily armed than their contemporaries – ships that could defeat any of their own type but capable of escaping a stronger foe.

That the Admiralty, involved in fighting Napoleonic France, had taken little note of the few American heavy frigates is understandable, as is the shock and embarrassment 14 years later with war’s outbreak in 1812 when their early successes ended the RN’s years-long unbroken string of frigate victories.

One of the factors credited with contributing to the American successes was said to be a deep pool of experienced seamen. A pool there was, but the USN was an all-volunteer force and by no means all available seamen volunteered. And while these men were skilled salts, relatively few of them had had any experience in fighting a ship. In fact, none of Constitution’s victorious captains had ever been in a ship duel, and their previous combat action had been bombarding Tripoli prior to Horatio Nelson’s epic Trafalgar victory.

When the war broke out in June 1812, Constitution was completing a post-voyage overhaul and enlisting a crew. The last crew member signed on less than three weeks prior to the 19 August meeting with HMS Guerriere and Captain Isaac Hull had been unable to do more than non-firing loading exercises with the great guns. Upon sighting one another in mid-afternoon, Captain James Dacres, RN, reportedly dismissive of his foe’s skills, decided to let his upwind opponent close.

Captain Hull’s cautious approach seems to have frustrated Dacres, so he turned on the wind, inviting close combat. Hull accepted the challenge and made for a position about pistol shot distance on Guerriere’s starboard quarter, his long guns and carronades double-shotted and any need for accuracy of aim eliminated.

After 15 minutes, Guerriere’s mizzen went by the board. There were two collisions subsequently, before both of Guerriere’s remaining masts fell and the battle ended. Finding he could not stem the flooding aboard, Hull removed everyone and blew his prize up. Constitution returned to Boston where two of her lower masts were replaced.

In his very brief report of what he termed ‘a brilliant victory,’ Hull brazenly lied that the action had taken only 30 minutes. (Two hours is more like it.) This fuelled the euphoria people felt in the surprise victory, and the journalists of the day quickly went to town. Hull also neglected to mention the two collisions, and went so far as to commission paintings of the action that reversed the ships’ positions so that knowledgeable viewers would not be led to wonder if such an event had occurred after the Briton’s mizzen fell.

William Bainbridge succeeded Isaac Hull in command of Constitution. He was a loser, having surrendered his first and third commands to enemies, and been at the center of a diplomatic embarrassment in his second.

He took Constitution to sea just as her sister, United States, was defeating HMS Macedonian. In the South Atlantic, he was some miles off Sao Salvador, Brazil, on 29 December 1812, when he encountered HMS Java, under the command of Henry Lambert, one of the RN’s most successful frigate captains, who already had won several victories in the Indian Ocean.

At first, Bainbridge turned away, thinking he was seeing a 74, but when he realized his error, turned back to engage. The duel opened at long range with Bainbridge discovering that his gunners couldn’t hit the side of a barn and Lambert getting in some telling broadsides. The American wheel was shot away and Bainbridge himself wounded in the thigh. No doubt with visions for further failure before him, he steeled himself, and using a midshipman for support, set about trying to retrieve the situation.

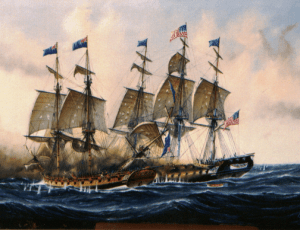

Java rakes Constitution

painting by Briton Geoff Huband.

He has heightened the drama by clouding the sky and roughing the waters (the actual day was sunny, the sea oily calm)

Marines were sent two decks below to man the rudder tiller, and midshipmen ordered there to relay. As Java was pulling ahead, to avoid a rake and gain time Bainbridge wore ship, reversing course and leaving Lambert to catch up again. The maneuver was repeated, but as Java was overtaking a third time, suddenly the Briton swung to starboard and raked her foe from astern.

Since Lambert could see no response and still had no indication of the damage he had done, he assumed his enemy had had enough and was seeking to flee.

On that basis, he maneuvered to regain his position to windward (larboard) of the big American, but made the mistake of not keeping his distance.

Simultaneously, Bainbridge desperately sought to shorten the range by sailing as close to the wind as he could. The net result was that American carronades came into play, and, double-shotted like their long gun compatriots, very shortly shot Java’s jib boom away.

As the Briton slewed to larboard, Bainbridge again wore ship to starboard until he was approaching Java’s larboard quarter. There, he delivered a broadside before falling away, having come dangerously close to becoming dead in the water.

When Captain Lambert regained control, he attempted to board his enemy but got tangled in the mizzen shrouds. While in that position, he had his foremast shot away, and Marine sniper Adrian Peterson, firing from a fighting top, hit the British captain with a rifle shot, giving him a mortal Nelsonian wound.

Constitution raked Java repeatedly before drawing off to make some rigging repairs and finally taking the surrender of a totally dismasted foe, which was scuttled after her helm was removed. The action had lasted about three hours.

As Hull had done, Bainbridge adjusted his report, making no mention of the rake. His prisoners were very generous in their comments about the treatment they received and the tender care given to the dying Captain Lambert, who endured until shortly after their arrival in Sao Salvador.

Bainbridge survived surgery a day or two later to remove splinters from his leg. Once back in the United States in February 1813, Constitution again had two lower masts replaced, together with six of her seven boats.

Constitution vs. Cyane and Levant

by American Tom W. Freeman. Levant’s stern is to the left and a wrecked Cyane to the right

Old Ironsides’s last war cruise didn’t begin until December 1814, when the British force blockading Boston was distracted by the grounding of one of its frigates. Charles Stewart was then her captain, and he had a quiet voyage until 20 February 1815, when, about 180 miles from Madeira, he encountered HMS Cyane and HMS Levant and accepted their challenge.

Stewart fought all of this battle within effective carronade range. With superb shiphandling, he divided his foes and his heavy firepower devastated them.

A question for me has always been why Sir George Collier’s squadron of two 44- and one 40-gun frigates subsequently met Constitution and let her escape. Sir George is not known to have left an explanation, and his terrible suicide by cutting his own throat precluded any interrogation.

To sum up: perhaps the greatest credit for the success of Old Ironsides ought to be assigned to Joshua Humphreys, whose superb design provided a fast, strong, and powerful weapon that made ordinary men winners.

BookPick: The Lifeboat, Courage on Our Coasts

Posted on October 7, 2013 2 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

The Royal national Lifeboat Institution is a venerable charity which I hold in the highest regard. And in this day and age, when people often seem so self-centred, it’s still manned by volunteers who put their lives on the line for strangers.

Incredibly, the RNLI has saved more than 140,000 souls since its foundation in 1824.

The 20th century saw the RNLI continue to save lives at sea through two world wars. Lifeboats moved from sail and oar power to petrol and diesel, and the first women joined their crews.

Recent years have brought a significant expansion of the service, with the introduction of RNLI lifeguards and the first lifeboat station on an inland waterway, both in 2001.

Last year alone some 7960 people were rescued by lifeboat crews. There are over 230 RNLI stations around Britain and Ireland with lifeboats ready to put to sea at a moment’s notice.

Photographer and crewman Nigel Millard and author Huw Lewis-Jones have produced a stunning visual tribute to the men and women of the RNLI. The over 300 photographs in this book were taken over the course of five years. Commencing on the Isle of Man – the birthplace of the RNLI – the book takes the reader on a clockwise circumnavigation of the British and Irish coasts.

As Prince William says in the Foreword to the book, ‘Each of the RNLI’s lifesavers, fundraisers, lifeboats stations and rescues has their own unique stories.’ This book honours them all.The next blog will be my first Guest Blog and I’m delighted to announce that it’s by Commander Tyrone Martin, a former Captain of USS Constitution.

James Craig: From Rotting Hulk to Pride of the Fleet

Posted on October 4, 2013 6 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

It’s always a joy to watch DVDs of tall ships and recently Kathy and I broached the rum cask to sit back and enjoy James Craig Sails Again. The 92-minute video is the story of the restoration of James Craig – an incredible example of dedication and Aussie grit.

A three masted barque, James Craig was built as the Clan Macleod in 1874. Her maiden voyage was to Peru and she had a busy working life, carrying cargo all over the world, rounding Cape Horn 23 times! In 1900 she was purchased by a Mr J J Craig from New Zealand and used as a general cargo carrier on trans-Tasman trade routes. In 1905 she was renamed James Craig.

By 1911 however, increasing competition from steam ships forced many sailing ships out of business. James Craig was stripped and used as a copra hulk in New Guinea.

When the First World War broke out a shortage of cargo ships brought the chance for a new life to the old girl. She was towed to Sydney for re-fitting – and work.

However this was short lived. In 1925 she was reduced to a coal hulk at the remote Recherche Bay in Tasmania, then abandoned when she broke her moorings in a storm and became beached.

In early 1972 a young Sydney-based maritime museum in search of a tall ship located her derelict rusting iron hull. For almost 30 years a small group of volunteers dedicated themselves to the heroic task of saving the ship; refloating the hull, towing it first to Hobart, then Sydney where restoration commenced.

Finally, incredibly, the story has a happy ending when off Sydney Heads in February 2001 she hoisted all 21 sails for the first time in nearly 80 years.

Today, as pride of the Sydney Heritage Fleet, she provides a unique connection with the days of sail and is the only operational barque in the world which regularly carries members of the general public to sea.

At the International Fleet Review in Sydney tomorrow James Craig will of course be out on the harbour. As well as wishing the Royal Australian Navy a very happy birthday I think we should all raise our glasses to one heck of a restoration!

James Craig

The DVD is available to purchase for A$10 plus p&p.

Enquires to info@shf.au Note: outside Australia you’ll need a multi-region player.

Huzzah: A Toast to Britannia!

Posted on October 2, 2013 7 Comments

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the start of training of British naval officers on the River Dart in Devon.

In 1863 the wooden hulk HMS Britannia was moved from Portland and moored in the Dart. In 1864, after an influx of new recruits, Britannia was supplemented by HMS Hindustan. The original Britannia was replaced by Prince of Wales in 1869, which was later renamed Britannia.

The splendid red-brick college at Dartmouth was completed in 1905 and the current commanding officer is Captain Jerry Kyd (one ‘d’).

Last weekend more than one hundred officers and cadets from BRNC marched through the Devon town of Dartmouth with swords drawn, bayonets fixed, drums beating and colours flying. No, it wasn’t an invasion but BRNC exercising its right of Freedom of Entry. It’s the first time in more than 50 years the college has done so since being given the honour in 1956. Freedom of Entry dates back to medieval times, a symbol of a close relationship between citizenship and military.

Over 3,200 cadets from 68 different countries have passed through the doors of the college in the past four decades alone. There’s a long tradition of training international naval officers at Dartmouth and the rolls include three twentieth-century monarchs! Many male members of the Royal Family have attended BRNC – The Duke of Edinburgh (who met his bride-to-be, Princess Elizabeth, here), The Prince of Wales, The Duke of York, Prince William.

In Kydd’s day there was a small naval college at Portsmouth but the majority of naval officers learned on the job. Admiralty regulations stated that a man had to have served a minimum of three years as a midshipman or master’s mate in the Royal Navy before qualifying for lieutenant, and have served a total of at least six years at sea.

Nowadays, officer training takes place ashore and afloat with opportunities to take up around 20 specialist officer roles from the six main branches of the Royal Navy – Warfare, Engineering, Logistics, Medical, Chaplaincy and Aviation.

There’s been some talk of proposals to close Britannia Royal Naval College but fortunately the security of the college now seems assured, at least for the foreseeable future.

Britain leads the world in officer training and I would have been very saddened indeed had Britannia gone the way of many fine institutions in today’s climate of budget slashing – and, on a personal note, I treasure the honour of having had the launch of MUTINY there.

Copyright notices

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice

In Kydd’s Footsteps

Posted on September 30, 2013 4 Comments

[To leave a comment go right to the end of the page and just enter it in the ‘Leave a Reply’ box]

Kathy and I greatly enjoy going on location research for the Kydd books and to date the series has taken us to all kinds of exotic places around the globe – from Antigua to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania).Was it our wanderlust behind the fact that it wasn’t until the eighth title in the series that the story was set in home waters, I wonder… Whatever the reason, writing that book highlighted to me just how strong the maritime heritage is in the West Country. But that’s the topic for another blog!

Recently, when two friends (and fans of the Kydd series) from the States had a short stay in Devon it was a perfect excuse to revisit two of the locations in The Admiral’s Daughter.

Our first stop was Saltram House, a George II era mansion near Plymouth. It’s one of the best preserved examples of an early Georgian house, and in Kydd’s day was the finest estate in the area. The actual name Saltram derives from the salt that was harvested on the nearby estuary and the fact that a ‘ham’, or homestead, was on the site before the Tudor period.Film buffs may have spotted the true identity of Norland Park in the film Sense and Sensibility. Yes, it was Saltram House!

In The Admiral’s Daughter, Kydd, now an officer and a gentleman, is invited to Saltram and approaches the grand estate with some trepidation:

‘The spare, classical stateliness of Saltram was ablaze with lights in the summer dusk and a frisson of excitement seized Kydd as a footman lowered the side‑step and stood to attention as he alighted. In a few moments he would be entering an existence he could not have dreamed of before and so much would hang on his motions of the next few hours.’

Kydd takes in the scene when he arrives:

‘It was a pretty village; the small harbour was central with its piers and little fisher boats in rows on the mud.’

In Polperro Kydd meets sweet Rosalynd and is then torn between her and the admiral’s daughter, Persephone Lockwood.

Polperro retains much of its history and character to this day. Take away the electricity supply and a few other trappings of modern life and the little village hasn’t really changed all that much. It’s one of the most charming spots on the Cornish coast and I heartily recommend a visit if you ever get a chance.

All too soon our friends had to depart and return to the States but I hope when they re-read The Admiral’s Daughter, as they were keen to do, they will find their visits to Saltram and Polperro have enriched their appreciation of Kydd’s world. I know Kathy and I certainly did!

I’d love to hear from readers who have visited other locales in the series.

Copyright notices

Saltram House: By Chilli Head from Weston-super-Mare, UK (Saltram House, Devon) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Every effort is made to honour copyright but if we have inadvertently published an image with missing or incorrect attribution, on being informed of this, we undertake to delete the image or add a correct credit notice